Toki Pona

Our columnist looks at the smallest language on earth—both deliberately simple and full of ambiguity—and explores its recent development and existing translations.

We have a winner for the smallest language on earth—it’s Toki Pona, and it is deliberately simple. Developed by Canadian linguist and translator Sonja Lang, the language was unleashed in the world in 2001. Lang says she invented it because she wanted to create a language that would promote simplicity and goodness.

Toki Pona contains just fourteen phonemes, which is less than almost all major languages in the world (English has forty), and the number of words in the language is a tiny 137 (the Oxford English Dictionary lists about 170,000 words currently in use in English). Practitioners of Toki Pona must be extremely creative: it’s up to them to create coinages for concepts not directly covered in the language. Speakers of the language have become amazingly adept at doing just that, and there is a dictionary that codifies thousands of such contrivances, but, even so, any aspiring Toki Pona speaker should expect a fair amount of ambiguity and confusion.

How exactly did this language come to be? Well, from the get-go, Pona-creator Lang seems to have had a natural affinity with language, growing up using French in her New Brunswick household while also using English with the world at large. She is reported to speak at least five different languages (one of them being Esperanto), and she seems to have familiarity with many more, including Finnish, Thai, and Arabic. She invented Toki Pona by examining the overlaps among the languages that she knew, trying to figure out what were the basic factors that one would need to construct a viable language.

To her surprise, when Lang put the language online in 2001, it resonated strongly with a core group of users and soon began to take off. During an event at the University of Colorado Boulder, Lang shared her belief that the language began to find its place when the online chat platform Discord became popularized—with the lengthy and complex conversations permitted via Discord, she saw the language really blossom into something complex. Another way Toki Pona has blossomed is by spawning other languages based off of it, including Toki Ma, an expanded version of the language; Luke Pona, a sign-language version of Toki Pona; Tuki Tiki, an even more minimalistic version; and Sitelen Pona, a character-based version of the language that has become the second-most popular written version of the language, after the Roman alphabet.

Because the language has such a small vocabulary, ambiguity reigns, and that’s a feature, not a bug.

Because the language has such a small vocabulary, ambiguity reigns, and that’s a feature, not a bug—this ambiguity is considered one of the language’s prime virtues and reasons for existing. To paraphrase Lang, it forces a speaker of Toki Pona to focus on the fundamental parts of things and not to get lost in the details, which I think is to her point of promoting what is simple and good. Or here is how Lang puts it in one of many examples drawn from Toki Pona: The Language of Good:

If tawa is used as an adjective, then this sentence says “I gave your car.” If it is used as a preposition, though, it could mean, “I gave the house to you.” So, how do you tell the difference? You don’t! (Insert evil, mocking laugh here.) This is one of those problems inherent in Toki Pona that there is no way to avoid.

As this quote might indicate, Lang’s manual of Toki Pona, titled Toki Pona: The Language of Good, shows us a person who is very much enamored of the philosophical underpinnings of words, and who naturally adopts a playful, slightly gnomic tone while doing so. (Reading Lang, it’s almost as if Yoda were a language instructor.) I can feel Lang’s thirst to imbue others with what I imagine is her creative spirit, hoping at the very least to open eyes to all the things a language can be:

It’s not so easy to adopt the way of thinking that Toki Pona requires. But be patient; eventually, even if you don’t agree with the ideas behind Toki Pona, it will at least broaden your mind and help you understand things better. Toki Pona is so much more than just a language.

Lang’s language philosophy also comes off as extremely nonhierarchical. She ends Toki Pona: The Language of Good by reminding users that Toki Pona really belongs to them, and thus they have the responsibility to use it creatively. That fact that this is indisputably true—no one can own a language, and it’s up to speakers to continually renew the linguistic reservoir—doesn’t take away from the generosity of spirit with which Lang encourages speakers of Toki Pona to make it theirs.

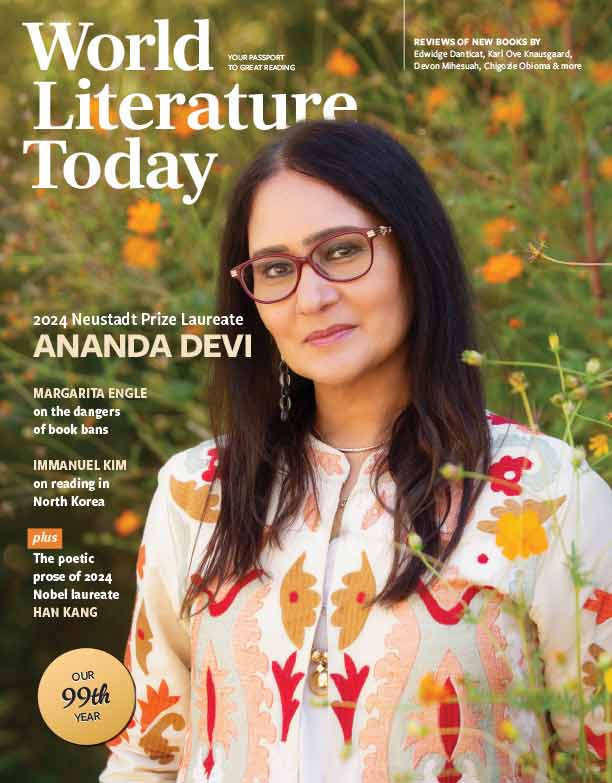

Since sharing her language in 2001, Lang has released three books for the Toki Pona community, and she has given each book a particular Toki Pona word as well as its own Sitelen Pona glyph. (Interestingly, the glyph for each book is derived from the book’s cover.) Pu is the word she gave to her first book, Toki Pona: The Language of Good, while ku is the word for her second offering, Toki Pona Dictionary. And the word su corresponds to her latest effort, a translation of The Wizard of Oz into Sitelen Pona.

When Toki Pona Dictionary arrived in 2014, the official word count of the language swelled from the original 120 to somewhere in the range of 181, with seventeen of the new additions being considered a “core” part of Toki Pona and the rest being relative rarities that may or may not be counted as canonical. The dictionary, which is about 400 pages in length, contains some 11,000 entries, translating English words into Toki Pona utterances and vice versa. Lang was clear to situate it as a documentation of the language as it had evolved up to that point and not a definitive source. Notably, this work offered multiple Toki Pona coinages for each English word (superscript numbers indicated the relative frequency of each particular coinage), pointing to the flexibility of the language, the contextual nature of its semantics, and the widespread community that uses it. As dictionaries go, it is less a proscriptive tool than a source of inspiration to help Toki Pona speakers invent their own coinages.

The arrival of Toki Pona Dictionary indicated that this language was one that would follow at least some of the trajectory of a typical natural language, and surprisingly (or not) Toki Pona has continued to follow that trajectory in other ways. For instance, a fascinating study found that Toki Pona conforms to a language axiom known as Zipf’s law, which states that the frequency of words in any given text will follow a regular series of 1, 1/2, 1/3, 1/n—that is, the second-most common word in a text occurs about half as often as the most common, the third-most appears about one-third as often, and so on.

This axiom has been shown to hold up for dozens of languages, and even though Toki Pona is radically different from the other languages that have been analyzed for Zipf’s law, this study seems to have found evidence that it still conformed to it, almost as though there were some underlying principle of all viable languages. The paper’s authors speculated on some fundamental aspect of human cognition, but they also noted that Zipf’s law has been shown to apply to other phenomena, such as “city populations, web traffic, or even the size of Pluto craters,” so maybe it’s all just nonsense created by overactive statisticians. (If you are confused as to how Zipf’s law can apply to something like Pluto’s craters, then we are in the same boat, but apparently it can and does.)

There are other ways that Toki Pona is being drawn into the linguistic fold of other more normative languages. It is being connected to the international web of translations, as books have been translated into Toki Pona by various members of the community, including The Little Prince, Aesop’s Fables, Siddhartha, works by Beatrix Potter, and Grimms’ Fairy Tales. There are also original Toki Pona creations that await their translation into other languages. At close to seventy thousand words, nasin Lanpan is considered the longest original work of fiction written in Toki Pona—this description of the work at Toki Pona’s official wiki, sona pona, makes it sound like some kind of mash-up of Nabokov, Thomas Bernhard, and David Mitchell:

nasin Lanpan is written in the first-person perspective of a narrator attempting to write a story. In the course of this effort, they distract themself [sic] with long tangents about their personal life and their cynical views of the world, making deprecating comments about the reader, people they know, and themself [sic]. They end up writing multiple attempts at conveying the story they want, including a run-on sentence of around 4,000 words. They conclude with a 100-line poem affixed with 123 footnotes scattered throughout the text.

I’d love to see someone try to create an English-language version of this book—given the highly ambiguous nature of Toki Pona, such a translation would be quite the interesting (and creative) task! In my research for this piece, I did not encounter any such formal translations, but I did find something close: tightening up the interconnections between Toki Pona and English, earlier this year Lang released a Toki Pona translation of The Wizard of Oz—a bilingual edition, with the original English translated into Sitelen Pona and then translated back into a very different English-language edition. Call it, perhaps, a creative translation that not only broadens the linguistic possibilities of Toki Pona but also those of English.

I love how the process inherent in this Toki Pona Wizard of Oz closes the circuit, going from English to Sitelen Pona back to a transformed English.

I love how the process inherent in this Toki Pona Wizard of Oz closes the circuit, going from English to Sitelen Pona back to a transformed English, in effect mimicking what I believe has been happening as speakers of English have learned to speak Toki Pona, and then brought that experience back into their native English. Its emblematic of how the philosophy behind this “language of good” has permeated other languages over the past twenty-four years, like a bit of dye diffusing throughout a glass of water. I am curious to know what happens in the world of Toki Pona next.

Oakland, California