Language of White Bones: The Secrets of Han Kang’s Poetic Prose

Like a clutch of words strewn over white paper.

Seoul, which I had last seen in summer, had frozen.

Turning to look behind me, I saw the snow already

sifting down to cover those just-made prints.

Whitening.

—Han Kang, The White Book, trans. Deborah Smith

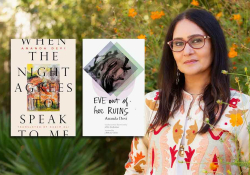

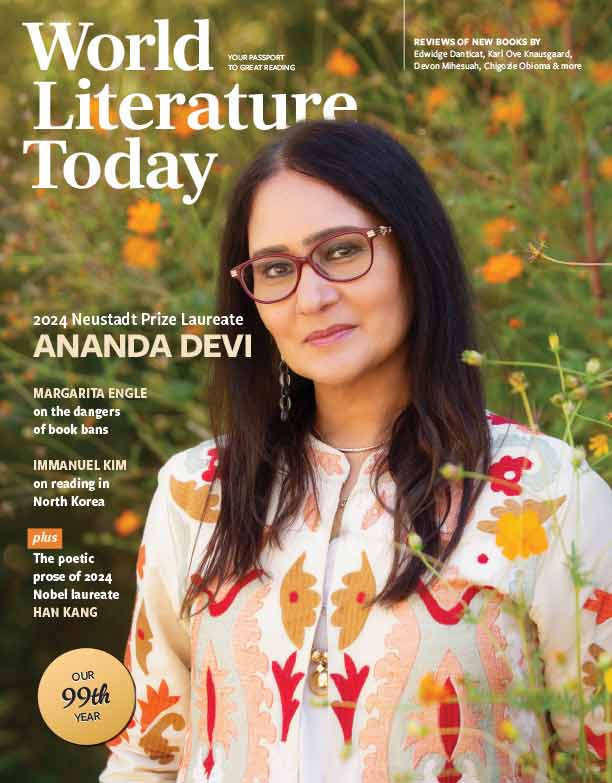

Han Kang, winner of 2024 Nobel Prize in Literature, the eighteenth woman, the third Asian, the first Korean to earn the prize: I heard the news while rushing to the funeral of my friend’s father. It was a sad, absurd, beautiful evening. In the morning, I had just finished writing a short essay about Anne Carson, a piece that would be published in the newspaper if she won the Nobel. My phone began to ring. Again and again, it rang constantly.

The Swedish Academy announced that the prize was awarded for Han Kang’s “intense poetic prose that confronts historical trauma and reveals the fragility of human life” and her “unique awareness of the connections between body and soul, the living and the dead.” In such an overwhelming moment, it came as no surprise that the Nobel committee specifically recognized her poetic style as an example of experimental innovation in contemporary writing.

In fact, her oeuvre does not adhere to the conventional grammar of the novel that lays out the causality of events and lives. Her works do not readily conform to the established norms of Korean national literature, which have usually been marked by male figures. Within the discourse of Korean national literature, the writings of Han Kang have been marginalized, and the national project and yearnings for the Nobel Prize veered toward the lionized male writers long after she gained international recognition as the recipient of the 2016 Man Booker International Prize. Some say that her literary achievements that finally led to the winning of the Nobel can be seen as a triumph over the very marginalization of a relatively young female writer.

During the short interview with the Nobel committee on that unforgettable October evening, Han Kang, however, said humbly that her writings are indebted to previous writers within the heights of Korean literature. I take it that her words are truthful, considering her sincerity. Han, who has trodden the narrow path of becoming an independent full-time writer after quitting a full-time professorship in 2018, is a writer who delicately shapes, kneads, and molds the Korean language. Running a tiny bookstore—Onulbooks in Seochon, an old village near Gyeongbokgung Palace in the middle of Seoul, which is temporarily closed as of now—she seems to never regret her decision to be a writer. At once gathering the scattered debris of history, checking facts, and searching for her novels’ materials, Han has dedicated her days and nights to reading, walking, and writing, persistently sowing the seeds of literature among common readers and planting the roots of literature in the common ground here in Korea. She has never relied on the familiar inertia of writing but continues to experiment with forms and develop new ways of telling stories connecting the dead and the living, crossing the boundaries of genre. That’s why on the evening when the stunning news arrived, I felt that the simple but profound lines of the Swedish Academy succinctly captured the essence of Han Kang’s writing.

❧

For me, Han Kang’s literature is a genre in its own right. In fact, she was a poet before she became a novelist. The literary trail she has followed is characterized by a tenacious poetic language composed of all-white bones blasting the past. They entirely penetrate her novels. Pitched in endless battle against the traumatic losses that humans must face, her poetic prose relocates the voices of the dead and the living, filling the gaps and crevices where official history failed to fill in its own writing with the tears, bitterness, and resentment of those who could not properly mourn the dead. For Han, the very act of writing serves to complete the unfinished act of mourning in the language endlessly calling the dead back to life. Those familiar with the logic and practice of writing novels realize that Han does not follow the conventional grammar of novels, such as laying out the causal chain of life. The evolution of Han’s experimentation with poetic voices reveals the concentrated power of her language, which forms a kind of empathic witnessing for all defeated beings in the passage of history.

The evolution of Han’s experimentation with poetic voices reveals the concentrated power of her language, which forms a kind of empathic witnessing for all defeated beings in the passage of history.

Sometimes her poetic prose pushes descriptions of reality to the extreme, to a level that readers find difficult to read. Some say it is ugly, some too bitter, too dark, too anguished. In her 2014 novel 소년이 온다 (A boy is coming), translated as Human Acts (2016) by Deborah Smith, Han focuses on the death of a middle-school boy, Dong-ho, in the turmoil of the 1980 Gwangju Massacre. As stated at the end of the novel, “Break open that moment and out of it will come massacre, torture, violent repression. It gets shoved aside, beaten to a pulp, swept away in the tide of brutality. But now, if we can only keep our eyes open, if we can all hold our gazes steady, until the bitter end.” In the original Korean, it’s more rhythmic and poetic: “Crushing the moment, a massacre arrives, a torture arrives, a forced repression arrives. They push, crush, and sweep everything away.” And the final line, which means that as long as we keep our eyes open, we will ultimately confront them, seems to be a stern reminder of a writer’s role in representing the cruelties of this world.

Born in 1970 in the city of Gwangju, Han Kang might have witnessed the tragic massacre if not for a change in her family. Just before the uprising, her father, the novelist Han Seung-won, moved the whole family to Seoul, and she later came to know about the tragedy from a book and photo albums her father secretly brought from Gwangju. She confessed in an interview that one night when she happened to open the book without her parents knowing, something slipped from her soul forever. It was the moment when an everlasting sadness and anguish settled in her mind and sensibility.

Near the end of Human Acts, the narration of Dong-ho’s mother shows the suffering of a fragile human being who endures her remaining years as the passing of seasons. “Winter passes, and spring comes round again. Spring sends me into my usual delirium; summer brings exhaustion and an illness I find difficult to shake off.” After Dong-ho’s death, she endures autumn and winter with stiffened joints and ice penetrating deep into her bones, into her heart. She lives with the ice, which never leaves her. Centering the absent presence of the dead boy in the novel, Han freely traverses large time spans and shifts the point of view from first, second, to third person. In her experimental style, which registers all the possible tones of different voices, Han performs a shamanistic ritual of bringing dead souls back to life. Just as Dong-ho’s mother breathes in the icy vapors, Han’s writing gains power in the very act of inhaling the final breath of the dead. The circulation of the living and the dead resembles the juxtaposition and arrangement of narratives, events, and lyric voices.

In an interview with Krys Lee on the occasion of Han Kang winning the 2016 Man Booker Prize, Han asserts that her writing begins with “burning questions” that disturb her, an interrogation of place, a desire “to explore human purity and strength more deeply” (WLT, May 2016). In confronting the normalization of vice and violence, Han bears the responsibility of a writer who wrestles with the limits of language, penetrating to its very core, mirroring the fate of human beings who have no other way to live but to endure. Han’s work conveys the feeling that small, fragile beings might sustain the world, connecting the thread of life “as tough as an ox tendon.”

Han’s work conveys the feeling that small, fragile beings might sustain the world, connecting the thread of life “as tough as an ox tendon.”

In The White Book (2016; Eng. 2019), a beautifully woven elegy of whiteness and meditation on grief, also translated by Deborah Smith, Han invites readers to follow the fragmented landscape of her mindset, facing the sadness of mortal beings, the defeated, the broken, the disappeared. Telling slant the grief of her mother, who had to repeat “Don’t die. For God’s sake don’t die” to Han’s onni (elder sister) as she lay dying two hours after birth, Han visualizes moments of impossible mourning. Whiteness in The White Book refers to language’s double and triple layers, at once the only color to represent fragility and dazzling moments of impossible representation, while at the same time the only possible way to capture the light, a moment of living. Han solves the dilemma using poetic prose, featuring eyes that see the “the precious young petals” concealed at the heart of a white cabbage and their “shining grains of dust,” both tender and tenacious.

❧

Han Kang made her literary debut as a poet in 1993, the same year she graduated from Yonsei University. The very next year, her short story was selected for the New Year’s Literary Prize, marking her auspicious literary debut in South Korea. Han’s first and the only verse collection, entitled I Stored the Evening in My Drawer, came out in 2013, twenty years after her debut. At the time, she had already published many novels and collections of short stories, including Love of Yeosu (1995), Black Deer (1998), Fruits of My Woman (2000), Your Cold Hands (2002), The Vegetarian (2007; Eng. 2015), The Wind Blows, Go (2010), Greek Lessons (2011; Eng. 2023), and Fire Salamander (2012). On the surface, it seemed like Han’s literary journey veered from poetry and went into the world of fiction. However, Han has always maintained a poet’s sensibility, and her distinctive fictional language is rife with the sort of poetic features that I call “the language of white bones,” like “a clutch of words strewn over white paper” (The White Book).

Han’s novels—full of poetic metaphors, leaps, and fantasies—dwell in a liminal space. Liminality, derived from the Latin word for threshold, marks a space and time between what was and what will be—a place of transition, a time of waiting and not knowing the future, a space between the familiar and the unknown. In Han’s works, it is the white space between the living and the dead, between the sadness of loss cemented at the moment of passing and the joy of life that nevertheless continues. From one of her early short stories entitled “Baby Buddha,” I’ve memorized the following lines: “[I] endured the winter, [I] rejoice in the spring, I sat there, repeating the words that came to me as if someone had whispered them to me. The dawn light slowly faded. A bird flew over the barbed-wire fence, spitting dry cries as it flew up to the blue mountains. Naked branches rustled in the wind, making the sound of brushing against the body.”[i] For Han Kang, the temporality of writing is similar to the passage above. Between winter and spring exists a liminal space: between the past tense of “endured” and the present of “rejoice.”

The in-between space is a long, chaotic period filled with patient waiting. Waiting is meaningful only when you do not know the result, when you do not recognize even the fact of waiting. Waiting with knowledge that something is coming is not waiting in a real sense. This explains the secret power of Human Acts, dealing with the Gwangju Massacre, and We Do Not Part (forthcoming in English), revisiting the Jeju April 3 incident (1948–49), in which Han weaves and connects the dead and the living, past and present, recollection, return trips, and unexpected meetings.[ii] To echo Walter Benjamin, “to articulate the past historically does not mean to recognize it ‘the way it really was.’ It means to seize hold of a memory as it flashes up at a moment of danger.”[iii] The unexplained vision of a feminine being resisting patriarchal violence in The Vegetarian transforming into a plant, or the voice of a dead boy speaking in sentences in Human Acts, cannot be explained within the grammar of conventional fiction. In another of Han’s climactic epics, The Wind Blows, Go, a search for memory—crossing the boundaries between beginning and end, present and past—presents overwhelming physical images that surround the mysteries of the universe and the origins of life.

❧

The amazing news from Sweden also summoned a long-forgotten poem, “A Letter,” that was published thirty years ago in the Yonsei University newspaper Yonsei Chunchu.

How are you, are you doing well all the time without getting sick,

I have wondered.

So hard to let go of one winter,

Leaving the road,

The road of flowers blooming and falling,

Spring snow rushes down, untimely in this March.

The whole winter was a time of fever,

Passing through the frozen nights and days,

I won’t forget

the tearful warmth of the little heated floor.

Who would dare say, on what basis, that this snow stops. It will stop, obviously. . . . Can’t you see this heavy snow, pouring down on the earth from the sky? Pine branches bent to breaking . . . that faded forest green, in this, this wind, with no walls to lean on, ah . . . this place, a place where even the way forward is buried.[iv]

In this epistolary poem, she painfully and painstakingly asks: Why is the last hope not cut off? in spite of the helpless vomiting of life, damn it, life, here and now, in such a frustrating faith, frustrating hope. Here we return to the originary moment of guilt that overwhelmed her. Reviewers saw in her lines the unique embrace of a radiating inner heat that swirls like the shamanic dance in a scene of exorcism, a fiery mass of passion and energy rich with the shape of what is to come.

For Han Kang, writing shapes “what is to come,” weaving questions, giving form, thinking, wondering, worrying, getting lost, detouring, coming back, dealing again and again with the question what it is to be human and what it means to live, . . . what passes, what disappears, what remains in the midst of loss. The process is not a linear progression—it is a movement of going forward, passing through the time of loss, crossing an impossible mourning. For example, the first poem in her poetry collection I Stored the Evening in My Drawer, “One Late Evening, I,” deals with the very moment when something is missed.

One

late evening, I was

watching the steam rise up

from the rice in the white bowl.

Then I realized

that something was gone by forever,

even now,

it is going by, forever.

I am going to eat rice.

I ate the rice.[v]

Here, the moments of sudden loss and mourning come together, layered, without notice. Time does not flow in a straight line, it percolates. As I eat, I realize abruptly that something has passed forever. While vaguely grasping that something is passing away, she eats nevertheless. What strikes me in this poem is not the feeling of shameful loss that permeates everyday activities. Between the line “something was gone by forever” (marking the past) and the ongoing “it is going by, forever,” there is an ambiguous hesitation—the poet makes it clear with the stanza division. Embracing the unidentifiable loss repeating throughout her life, the lonesome speaker eats rice. Like the act of crossing an irreversible rift, this repetitive action would go on till the end of life. We know that it forms a mystic ritual of life, providing energy to sustain the world filled with loss “as tough as an ox tendon.”

In another poem in I Stored the Evening in My Drawer, “Mark Rothko and I—Death in February,” the speaker comes face to face with a Rothko painting.

With nothing to announce in advance,

there is no relationship between Mark Rothko and me.

He was born on September 25, 1903,

died on February 25, 1970.

I was born on November 27, 1970

and am still alive.

Sometimes

I just

think of the time of nine months

separating my birth from his death.

Only a few days after that early morning

when he slashed both his wrists

in the kitchen attached to his studio,

my parents intertwined their bodies

and soon after a speck of life

must have lodged inside the warm womb.

While in the late winter New York cemetery

his body must not yet have rotted.

It’s not something mysterious,

it’s something lonesome.

Inside a pink womb

I must have been lodged as a speck

whose heart had not yet begun to beat,

knowing nothing of language,

knowing nothing of light,

knowing nothing of tears.

When a crevice-like February

between death and life,

was enduring,

endured itself and finally was being healed.

When his hand must not yet have rotted

in the half-melted, even colder ground.[vi]

Born in November 1970, the poet believes that she shares a similarly shaped soul between death and life with Mark Rothko, the painter who died in February 1970. The painter chose death at the moment the poet-speaker was conceived as a speck inside her mother’s womb. The painter entered the space of death at the moment she came into existence. It means that her life was born out of inscrutable darkness, “knowing nothing of language, / knowing nothing of light, / knowing nothing of tears.” Life born from death, from darkness. Before the silence of the great abstraction, the speaker of the poem realizes the mystery of life like a rite of passage. In other poems, it becomes the ritual of the “first soul,” a voice that finally makes what cannot return visible. Seeing the inside of the painter’s soul, a crevice-like February between death and life, the process of enduring is completed as the form of being healed.

Han Kang’s work is poetic because it is not pure and untainted—it is sad, defiled, helpless, vulnerable. It is poetic because its rhythms are beautiful, because it builds up something after dismantling it, salvaging something from the ruins and debris, from the degraded, from the damaged. Rhythm for Han arises from a physical, organic mimesis of the suffering body echoing the rhythm of breath. Han’s work is poetic because it is sensuous, not allowing for any ornamentation in its restrained rhythm. The understated sensation is cold and bitter rather than warm and kind. Her work moves forward by the power of images, not by the force of narrative. Han’s process of weaving the language of white bones allows her work to have its own specific body.

Rhythm for Han arises from a physical, organic mimesis of the suffering body echoing the rhythm of breath.

In “Anatomy Theater 2,” the speaker says: “I have a tongue and lips // Sometimes it is difficult to bear them.” Han gazes upon the fragility of life, on small and delicate things, wrestling with human cruelty and human dignity, exemplifying an excruciating inner struggle. The ancient Greek word for poetry, poiesis, means the act of making or creation. If Han’s poetic style makes something, it comes from the very acting of gathering, remembering, and connecting fragmented memories and scattered images of history. Her work is the space where our dead, nameless, buried beings are all invited here now.

For Han, therefore, writing and suffering are one and the same. Writing is a voluntary entrance into the midst of terrible pain, inevitable suffering. Suffering is “a passivity that is more passive than passivity,” writes Emmanuel Levinas, but the “I” who voluntarily suffers is an active subject, not a passive one. It is a sturdy determination: I will not shrink from the suffering of the dead who are enveloped in my body, I will never say goodbye to them. Han’s poetic prose dwells in this promise. The language of white bones blasting the past marks the essence of her poetic prose. Here again, I turn to Benjamin.

A Klee painting named Angelus Novus shows an angel looking as though he is about to move away from something he is fixedly contemplating. His eyes are staring, his mouth is open, his wings are spread. This is how one pictures the angel of history. His face is turned toward the past. Where we perceive a chain of events, he sees one single catastrophe which keeps piling wreckage and hurls it in front of his feet. The angel would like to stay, awaken the dead, and make whole what has been smashed.[vii]

For Benjamin, the storm is blowing in from Paradise; it has got caught with such a violence that the angel can no longer close his wings. “The storm irresistibly propels him into the future to which his back is turned, while the pile of debris before him grows skyward. This storm is what we call progress.” For Han Kang, the storm is what we call literature. In the core of her prose, we see the wings of poetry spread, gathering the debris of history.

❧

“I’m the kind of person who connects with the world through what I write,” Han remarked at the Hyundai Pony Chung Innovation Award ceremony on October 17, 2024. “So, I hope to continue to write as I have been and meet readers in my books, and right now I’m trying to finish a novel I’ve been working on since this spring.” Shortly after the groundbreaking news of the Nobel hit the Korean peninsula, she decided not to give any official press conference celebrating the prize out of concern for people who are suffering and dying in the world.

Han is also a singer-songwriter. Listening to her song “Even If You Said Goodbye” (안녕이라 말했다 해도), one comes to know that even in the deepest and most desolate darkness there is light, simply because we are here, now.

Somebody who said goodbye

Somebody who threw everything away

Somebody who is not comforted

You are that kind of person

But it’s time to live

Time to live

Even if you said goodbye

Even if you threw everything away

Even if you’re not comforted

You’re here and now

It’s time to live now

Time to live

Time to get up and walk

It’s time to get up and walk

(Somebody, hold my hand)

It’s time to get up and walk

(Now take my hand and let’s go.)[viii]

Seoul

[i] Han Kang,내 여자의 열매 (My woman’s fruits) (Moonji, 2000), 174, my translation.

[ii] The Jeju uprising was a series of violent clashes and brutal suppression that occurred on Jeju Island beginning on April 3, 1948, leading to the deaths of an estimated ten thousand to thirty thousand people over several years.

[iii] Walter Benjamin, “Theses on the Philosophy of History,” in Illuminations, trans. Harry Zohn (Schocken Books, 1968), 255.

[iv] Han Kang, “Letter,” Yonsei Chunchu, November 23, 1992, my translation.

[v] Han Kang, 서랍에 저녁을 넣어 두었다 (I stored the evening in my drawer) (Moonji, 2013), 11, my translation.

[vi] Han Kang, 서랍에 저녁을 넣어 두었다, 16–17, my translation.

[vii] Benjamin, “Theses,” 257.

[viii] Han Kang, 안녕이라 말했다 해도, my translation.

Editorial note: Read a review of We Do Not Part from this same issue. Eun-Gwi Chung’s essay “‘Tough as Ox Tendons’: Korean Literature and Returning Catastrophe” appeared in the March 2017 issue of WLT.