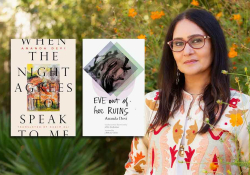

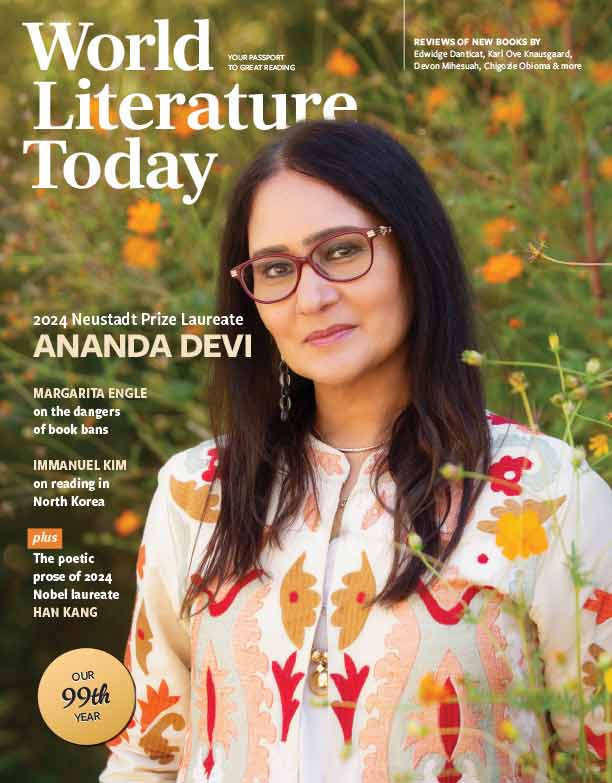

A World of One’s Own: A Tribute to Ananda Devi

As the juror who nominated Devi for the Neustadt Prize, Fabienne Kanor made a passionate case for her work when the jury convened on the University of Oklahoma campus in October 2023. Although she could not attend the Neustadt Prize award ceremony, Dr. Kanor wrote the following encomium for this issue’s cover feature.

For a long time, I would fall asleep with this domestic scene in my head: an interior, a room bathed in dawn’s early gleam with a louvered window showing a sliver of the garden, a table and chair, a teapot and cup, a bin overflowing with crumpled paper, a lamp for reading, a screen for adornment, a sofa for relaxation, books arranged by size or color, an empty vase, and, just in case, a pair of shoes. And then this woman, fully present, in a corner. Not sitting, not lying, but standing. Waiting, dressed to get up and about. And I see her walk, yes, barefoot to the window to take in the night’s lingering chill.

When she woke, it was four in the morning. She woke alone. The house was asleep. She woke alone, as always, alone as she was every time she set to making islands, bays, neighborhoods, roads, hills, cars, traffic lights, turns, accidents, bedrooms, night-pots, families, arguments, ancestors, specters, shadows, survivors. Alone as she was every time she set to meting out love or death, peace or struggle, freedom or captivity. She has never wanted for any other soul while bringing her worlds into the world. She has always known that writing is, at heart, a bed in a room. To lie in, to sleep in alone. In silence, thus, she has left the room, gone to the kitchen for something warm to eat, then rushed to lock herself in her office. To keep out all who would enter. Who would interrupt her morning. There’s no sharing the act of writing with others. No stopping it midway like a card game. Cooperation and compromise are for her dealings in daily life. Negotiations and deceit, with other people.

This utterly self-possessed, utterly self-collected woman is always at my side, has always been from the day I fell into writing. She is the specter on my shoulder as I write, the spirit who ensures that I fulfill my mission solemnly, steadfastly.

Were I to give this witch a human guise, I would give her the face of Ananda Devi, I would give her those delicate hands that do not tremble at killing off characters, those eyes that do not waver, like a brush fire that starts small before it swallows all, those timbres that do not quaver but rise and fall like a swelling wave in the Indian Ocean, those feet that do not ever stand bare before me yet in my mind bear wings like that archaic Greek messenger, or hooves like the she-devils of my homeland.

Were I to wrest secrets out of her, I would say: Tell me about your sorcery and your wordsmithery. Tell me what you see when a story comes to you, tell me which words reach you first, tell me where you stow your fears before diving in, tell me whether you feel a shiver run down your whole body as I do, tell me, whether you feel fear at all, what that fear is like: does its maw gape like that of the monsters you sometimes evoke? Does it have a tail and paws, fur and claws like a beast? Does it eat men? What does it do with their hide and their heart? Does it feed on grains of sand, on primeval forests, on savannahs? Does it let out a long, raucous hyena’s laugh? Does it spare you or go for the kill?

Do you believe that your stories will become engraved in the memory of this world, will become the memory of this world?

And if what you feel is not fear, then what is it? Tell me what comes over you when you create. Tell me what your body bears and where in itself that is held. Tell me what most haunts you. And tell me what is in your head when your hands stop and you rise from the table. Do you wander like the madwoman who stayed not far from my grandmother’s house? Back then, we would have said she was visited by spirits, or crushed by an impossible love. Her badly dyed hair hung over her eyes. Her voice, when it could be heard, was a lament. Her name was Marialine. You know our names . . . said in a go, with no hyphens. Tell me whether it’s she, that neighbor in Montgérald, that you take after when you, called however briefly away from your work, leave your office and return to your family and to that world, to daily life as wife of, mother of, daughter of, citizen of . . . Tell me how you stay standing, how you hold yourself together, how you survive this daily life with its rules and constraints not of your making. And will you please tell me what it is you hope? What will become of these stories that you have shaped so steadily? Do you believe that they will become engraved in the memory of this world, will become the memory of this world? That readers will go on savoring them once love, peace, wars, houses, night-pots in houses, roads, turns, hills, rivers, seas, volcanoes, libraries no longer exist? They will be read to experience infinitesimal human stories and infinite-seeming colonial histories alike.

In your books, havoc and heaven dance a pas de deux. In your books, a pas de deux plays out between the poor and the rich, vice and grace, grime and the perfume of flowers, chaos and order, men and women, the old and the young, slaps and hugs, drought and sweat, fire and ice, undercurrents and overwhelming forces, dreamers and souls who have lost all hope. When I was little, I thought that literature was created to instill wisdom. You showed me how silly I was. You showed us transgression. With you, I die from a single blow and come back to life in a thousand pieces. With you, my feet grow back where my head had been, my arms have six arms, my belly a million orifices. With you, I have learned of temptation. When I am asked why I so love reading you, I often reply that there is no explaining it. That when I read you, I am not reading; I am living, daring to live everything. It is like dancing in the rain or donning a swirling dress, like wishing for the love of a man sure to hurt you or the death of your neighbors or your cat or even your children, like leaping off a cliff into the void, like laughing maniacally midgathering, or finding a rip in your pants or a run in your pantyhose, or falling down in front of everyone, like standing in heels while blowing bubble gum.

Let me say to you the very words you said to me one day, the day that I told you I was flying to Oklahoma to champion your name and defend it like hallowed ground: “My island is my DNA, as much as my parents. I sometimes say I write in my mother’s voice, but I think it is also in my island’s voice.” Those were your words, and they make me think of Aimé Césaire and what he proclaimed and carried out in his Notebook of a Return to the Native Land: “My mouth shall be the mouth of those calamities that have no mouth, my voice the freedom of those who break down in the prison-holes of despair.” Do you remember that line? Are your words kin to his? Do our islands give rise to the same drives, the same vows? What does it mean, for you, to be the voice of your island? Are you the mouth of your heroes—Saad, Eve, Clélio, Savita, and all these poor souls with no rights or place on this earth? No. I think that your words go beyond the political, that they verge on the cannibalistic. I think that, in embracing your island, in inhaling it, you swallowed your island whole. That it lives on in your belly, your fingers, your mouth, your tongue. That your Mauritius is no simple, impersonal land; it is your deeply personal landscape.

In embracing your island, in inhaling it, you swallowed your island whole.

Let me end on that domestic scene: When I was little, I dreamed of a room of one’s own replete with books, and cats, and solitude. Never a bed for two, or a row of pots and pans along a wall, or diapers to be changed, or work to be done. When I was little, I dreamed that a woman who wrote had no homeland, no body, no needs, no limits, no family vault, that a woman who wrote had all time and space to herself. When I got older, I kept believing in this dream, and, with every book of yours I open, I believe it all the more. I see you, not sitting, not lying, but standing and unwearying, busy doing all that the writing of great books calls for: readying the tools, laying the foundation, clearing the way, digging down and down until the letters you type become walls, bays, neighborhoods, roads, hills, cars, stoplights, turns, accidents, bedrooms, night-pots, families, arguments, ancestors, specters, shadows, and survivors.

Translation from the French