How Many Ways Can Something Be Untranslatable?

From the missing work of Sappho to Lucy Ellmann’s thousand-page, stream-of-consciousness novel Ducks, Newburyport, our columnist considers the linguistic, cultural, and human challenges to translation.

Lately, I’ve been considering ways of expanding this column from exclusively focusing on untranslatable words to exploring broader notions of the untranslatable—books that pose the biggest translation challenges, languages that are the biggest reach for bringing into English, regions, concepts, cultures, and other things that defy attempts to port them between languages. Imagining all the potential subjects that might fit into these categories has made me wonder about the many ways that we can construe the notion of the untranslatable.

First, some framing of things. In his paper “Literary Translation: Old and New Challenges,” scholar Tawfiq Yousef groups translation challenges under three headings: linguistic, cultural, and human. The first two have to do with the difficulty of moving concepts between languages and cultures, whereas the third he defines as “the barriers facing literary translation including lack of government funding, poor literary translator training, language and cultural hegemony, cultural insularity, and indifference towards translated literature” (an interesting, and valid, notion of untranslatability). The paper is filled with interesting ideas about what factors defy translation, and readers are encouraged to seek it out, but for now I will only draw from it in order to borrow Yousef’s scheme of linguistic, cultural, and human translation challenges as a broad way of summarizing various factors that make translation difficult.

Under Yousef’s “linguistic” heading, we might hold space for texts that pose particular translation challenges. We could arrange those texts on a spectrum from linguistic simplicity to complexity: both the exceedingly simple and the extremely complex, I would argue, pose their own translation challenges. For instance, on the complex side of things, there are books like Lucy Ellmann’s Ducks, Newburyport that are said to defy an attempt to translate them because of their extreme length, denseness, inventiveness, wordplay, and encyclopedic nature. An article at the Publishing Post discussing this book in particular asked how a translator is to approach something like the following, which is drawn from Ducks, Newburyport’s thousand-page stream-of-consciousness single sentence: “The fact that we’re about due for another blizzard ourselves, gizzard, wizard, buzzard, zigzag, ziggurat, mosque, piecemeal, peacetime, four-foot sword . . .” Indeed, just imagine trying to figure out how to render language like that into another tongue, and to do it for one thousand pages—that would border on the impossible!

If Ducks, Newburyport is at one end of the linguistic complexity spectrum, then perhaps a haiku would be at the other end, posing a very different kind of translation challenge that revolves around the utter simplicity of the form. Demonstrating this point, scholars Gohar Ayaz and Muhammad Ali Khan brought together eleven translations of the Japanese poet Matsuo Basho’s famous haiku “Furu ike ya / kawazu tobikomu / mizu no oto” (drawn from the book One Hundred Frogs, which has well over one hundred translations of this poem). Just eight words long, depicting a frog that leaps into a pond, this haiku nonetheless supports so much poetic translation creativity, demonstrating the immense space Basho has garnered with such a beguiling form. This is a different kind of untranslatability—something that is so simple and perfect supporting so many “right” answers to the question of how to translate it. And it shows that we needn’t have a thousand-page postmodern novel to challenge notions of translatability.

If Ducks, Newburyport is at one end of the linguistic complexity spectrum, then perhaps a haiku would be at the other end.

Moving into questions of culture, one might consider the idea of linguistic and cultural remoteness: as Yousef notes, the question of a language’s distance from other more centered languages can often implicate matters concerning “the balance of power between different countries or, more specifically, between different cultures.” A fascinating example of this would be Basque author Bernardo Atxaga, largely untranslatable simply because the language he writes in, Euskara, is what’s known as a linguistic orphan, cut off from the other languages of Europe.

Moving into questions of culture, one might consider the idea of linguistic and cultural remoteness: as Yousef notes, the question of a language’s distance from other more centered languages can often implicate matters concerning “the balance of power between different countries or, more specifically, between different cultures.” A fascinating example of this would be Basque author Bernardo Atxaga, largely untranslatable simply because the language he writes in, Euskara, is what’s known as a linguistic orphan, cut off from the other languages of Europe.

Very few people speak this language—estimates range at around one million—meaning the chance that someone will translate from Euskara into any given other language is quite small. Why exactly Atxaga would choose to do this (when he is able to write perfectly well in Spanish) is a very interesting question with some revealing answers.

Atxaga originally chose to write in Euskara for largely political reasons: at the time it was under threat of being extinguished by the Spanish government. His ability to self-translate his books into Spanish was central to his viability as an author and Euskara’s viability on the world literary stage. From the beginning of his career, Atxaga has undertaken to self-translate his work (with the assistance of hired translators) into Spanish, making it more possible for his work to then reach audiences and languages far outside the Basque lands. This choice was a very meaningful one, indeed, as recounted by scholar Harriet Hulme in her book Ethics and Aesthetics of Translation:

In 1989, Obabakoak was nominated for the Spanish Premio Nacional de Literatura (National Prize for Literature). While nominated texts can be written in Castilian, Catalan, Galician, or Basque, they must be translated into Castilian before they will be considered by the jury, a reality which, as César Domínguez notes, somewhat ironically represses the very diversity of the literary system which the prize purports to represent. Atxaga complied with this request, hiring three different translators to help him translate Obabakoak into Castilian in order to ensure that it was ready in time, and then proof-reading and creating a text from these different versions. Obabakoak was named that year’s winner. As Domínguez comments, the “award of the prize was, therefore, indissolubly linked to that (self-)translation to Castilian.”

A full discussion of Atxaga’s decision to write in Euskara is beyond the scope of this essay, but readers are encouraged to seek out Hulme’s book for the broader story, as it is quite interesting. I will simply say here that Atxaga’s story speaks in powerful ways to the ways that “human” barriers can overlap with linguistic and cultural ones, as well as the ways that existing power structures are bound up in questions of what is and is not translatable.

To push a bit beyond the example of Atxaga, an extreme version of linguistic and cultural remoteness are the languages that we can no longer read, even though we do know the identity of the language we are dealing with. Among those would be Linear A (once used on the Greek island of Crete); Harappan, dating to about 2000 bce to a civilization that was then thriving in India’s Indus Valley; Elamite, a language that came into use around 2600 bce in the region of what is now Iran; and Rongorongo, a language that was likely once used on Easter Island. Any texts from these languages would be necessarily untranslatable simply because we no longer have the capacity to read them. This moves beyond the question of humans and our needs and preferences to implicate something much more fundamental—the forces of time and decay to which all human endeavors are subjected.

To continue pondering this question of linguistic remoteness, time, decay, and the role of the human in these processes, we might turn to a different kind of remoteness, one that borders on Yousef’s “human” category of translation challenges: namely, the impossibility of translating texts that simply do not exist because humans have failed to preserve them over time. For example, consider the Ancient Greek poet Sappho, of whose poetry all that remains is an estimated 3 percent of her complete work, consisting almost completely of fragments.

Sappho’s poetry survived for over one thousand years, from her death in 570 bce all the way until at least the ninth century ce—apparently, in the end, those in control of deciding what literature to preserve in the precious space granted to them determined that her poetry was not worthy of continued copying. That decision rendered her work untranslatable. While discussing the impossibility of translating the lost words of Sappho, Anne Carson writes,

There are two kinds of silence that trouble a translator: physical silence and metaphysical silence. Physical silence happens when you are looking at, say, a poem of Sappho’s inscribed on a papyrus from two thousand years ago that has been torn in half. Half the poem is empty space. A translator can signify or even rectify this lack of text in various ways—with blankness or brackets or textual conjecture—and she is justified in doing so because Sappho did not intend that part of the poem to fall silent.

In just four hundred pages, Carson translated everything then known of Sappho in 2002 (other poems have since surfaced). This included many poems that have been reduced down to a single word—imagine the weight of that, an entire unknown poem sitting on just one word, a very different kind of translation challenge. In order to bring some visibility to the untranslatable, Carson used brackets to indicate what had been lost.

Imagine the weight of that, an entire unknown poem sitting on just one word, a very different kind of translation challenge.

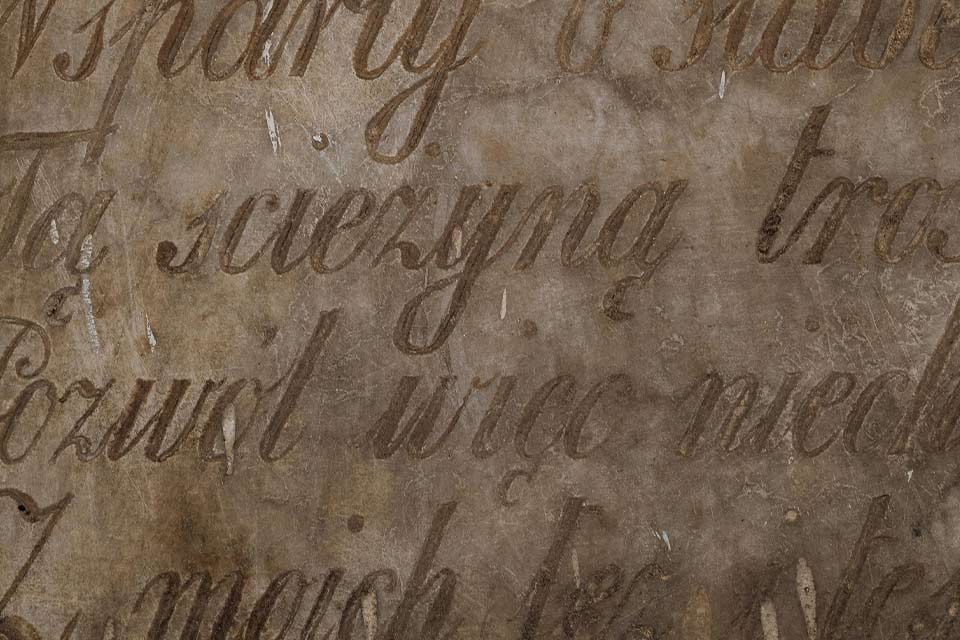

Perhaps conceptually connected in some meaningful way to the lost words of Sappho would be the books that are untranslatable because we don’t actually know what language they are originally written in. An example of one such item would be the so-called Voynich manuscript, named after Wilfrid Voynich, a Polish book dealer who purchased it in 1912. The books’ many hundred pages are filled with writing, but no one has ever figured out what it says or what language it is written in. Carbon dating has placed the manuscript’s vellum pages in the early fifteenth century, and statistical analyses have demonstrated that the manuscript exhibits patterns consistent with real languages, so it seems unlikely to be a hoax. Various explanations have been proposed, from a cypher or shorthand to a fever-dream stream of consciousness in an invented language to even a very obscure natural language. In spite of these proposed explanations, no one knows what the language in the manuscript says, if indeed it is a language that does say anything at all.

It is my belief that looking at extreme cases can often shed light on the great majority of cases that sit more toward the median of existence.

In coming installations of this column, I hope to explore some of these various concepts of the untranslatable and to continue being open to broader ideas of what an impossible translation might look like. It is my belief that looking at extreme cases can often shed light on the great majority of cases that sit more toward the median of existence, as well as be an enduring source of curiosity, fascination, education, and pleasure. I hope this column will inspire all these and more in the coming months.

Oakland, California