Transnational Transmission: A Conversation with North Macedonian Poet Andrej Al-Asadi

Born in London in 1997, Andrej Al-Asadi is among the foremost young poets writing in Macedonian today. In a conversation with Peter Constantine, he discusses his multicultural background and the influences that have inspired his work and that of other contemporary Macedonian poets.

Peter Constantine: You were born in London, your grandfather was from Iraq, and you are considered one of the most visible young poets writing in Macedonian today. Would you say that your multicultural background has fed the themes and stylistic approaches of your poetry?

Andrej Al-Asadi: With a background like mine, with genes and family from around the world, it’s inevitable that you notice parallels and draw connections between what could look like disparate cultures. That’s especially true for a poet, whose responsibility is often to see similarities or unities behind what appears to be distinct and dissimilar in everyday life. My multicultural background and my poetry feed into each other as a creative machine producing new ideas and motifs as well as the language to convey them.

Reading poetry from a variety of traditions, I found the same preoccupations recurring across nations and eras, and understood them to be essentially human rather than culturally specific. My earliest poetic influences were the classics of English literature. It might not be apparent within my own style or structure, but I was overwhelmed by something more fundamental in this tradition, that being its concern with the human condition.

At the same time, I was interested in my family background and began to learn more about Arabic and Persian verse, and then the Macedonian tradition, and I saw that these seemingly different traditions were in fact very similar. I found in modern Macedonian literature and Sufi poetry those ever-present subjects again: humanity, love, forgiveness, and the constant search for happiness. To Donne or Blake these may have been particularly English and Christian subjects, but I was able to understand them within a much broader context, and that’s how they’ve emerged within my own work.

Constantine: How did you personally come to poetry? Was there a sudden moment or situation, some sort of turning point in your life?

Al-Asadi: There was no definite single turning point in my life that brought me to poetry, because my poetry has always been something beyond conscious decision-making. I see my verses as a revelation or as a “transmission” from above and through me to the paper. I get inspired and lose my mind. I start writing and forget everything around me. That’s the way even the first poems appeared on paper, and that’s how they appear to this day.

I had to find some outlet for that inspiration, and in that respect there were of course early influences that might be regarded as turning points, but as I see it, it was more that they opened the “Doors of Poetry” to me. The first was Jim Morrison and his poetry on the Doors’ albums. My first amateur writing endeavors, in imitation of Morrison, were song lyrics accompanied on guitar, which unfortunately I have never published. The next was the great poet William Blake, especially his Songs of Innocence and Experience and The Marriage of Heaven and Hell. The last one, which finally cemented my will and drive to write verses, was Allen Ginsberg, who consequently led me to Beat authors like Jack Kerouac, Gregory Corso, and Amiri Baraka. But I must say that poets like William Shakespeare, John Donne, William Blake, and Edmund Spenser had perhaps the most significant impact on my initial writing enthusiasm.

Constantine: It is interesting that you mention classic English poets as an early influence. Could you say more about that? Your early poetry seems to have a very modern voice. Were you affected by any specific aspects of traditional English poetry?

Al-Asadi: Indeed, English poets were crucial for my early poetic development, to begin with as a reader. I was astonished by Renaissance poets like Spenser, Shakespeare, and Donne. Donne’s Holy Sonnets in particular stirred my interest in those universal poetic themes of divine love, penance, and death. More than any specific formal quality, these poets put me in a frame of mind to read and respond to other writers, like Blake and the Beat poets, and then Tasawwuf (Sufi) poets, including Niyazi Misri, Rumi, Al-Hallaj, and Hafiz. English poetry was in some sense a stepping stone. I later found many parallels between the traditional English poets and the first and second generations of Macedonian poets, which helped me immensely in crafting my style and finding a unique poetic voice.

The English Renaissance poets put me in a frame of mind to read and respond to other writers, like Blake and the Beat poets, and then Tasawwuf (Sufi) poets, including Niyazi Misri, Rumi, Al-Hallaj, and Hafiz.

Constantine: Northern Macedonia being a young country, I am not sure what you mean by the first and second generation of Macedonian poets. How are these generations defined?

Al-Asadi: Macedonia (for me, it will always be “Macedonia”) can boast of a poetic tradition dating back to the fifteenth century with traditional folk verse full of ancient Macedonian, Byzantine, and Slavic elements. In our country, the “generations” are determined from the group of more significant modern poets emerging right after World War II, when the Macedonians finally grasped the opportunity to establish their sovereign state and decide their own destiny. This first generation of Macedonian poets is famous for remarkable and gigantic poetic figures such as Aco Šopov, Blaže Koneski, Gane Todorovski, and Slavko Janevski. The second generation of Macedonian poets would be those who emerged in the 1950s, like Ante Popovski, Srbo Ivanovski, and Mateja Matevski.

Constantine: To what do you attribute their parallels with English literature?

Al-Asadi: Many of the great Macedonian poets read the same English poetry I did, and some of them translated them into Macedonian. Aco Šopov, one of our most prominent poets after the Second World War, was among the first translators of Shakespeare’s sonnets directly from English into Macedonian. One could say that he was very much influenced by Shakespeare and other classical British writers. All of our poets certainly read the English greats—Donne, Blake, Byron, Shelley, Keats, and Coleridge—often in the original English or in Serbo-Croatian, because in the postwar era that was the language into which they had mainly been translated, a legacy of the former Kingdom of Yugoslavia.

If one carefully reads the first and the second generation of Macedonian poets, I would say that one can easily spot some significant similarities between them and the classical English poets in style and form. Mihail Rendžov, who came of age in the 1950s, is particularly noted for developing the Macedonian sonnet form and the sermonic style, redolent of John Donne’s poetry. More recently, Dragi Mihajlovski translated many of the British greats into Macedonian, which has definitely influenced younger generations of poets.

Constantine: I find it fascinating, and surprising, that this postwar generation of modern poets would be reading the nineteenth- and pre-nineteenth-century British canon so enthusiastically while so many of their contemporaries around the world were reading postmodernist and Beat poets. Postwar Greek poets, for instance, were particularly interested in contemporary French and Italian movements. Did the Macedonian poets’ focus on traditional British poetry disconnect them from international literary movements?

Al-Asadi: On the contrary, they were deeply connected with international literary movements. The English poets were only a small part of the pantheon our first three generations of postwar poets were reading, albeit a significant one. Many of them were also inspired by Russian verse and authors, surrealists, the futurists, and revolutionary poets. The first and second generations of Macedonian poets translated these as well and held famous festivals like the Struga Poetry Evenings, in which Brodsky, Hughes, Auden, Ginsberg, and many others participated. At the same time, they were actively working for the international promotion of modern Macedonian verse and were themselves translated into English, French, Russian, Serbo-Croatian, etc.

Two Poems

by Andrej Al-Asadi

translated by Viktoras Iliopoulos

Refugees (Selam aleykum Europe)

pebbles like cuspids under heels

and hardened sweat under armpits

where thirsty flies cling

with dull eyes

they go on begging

for a dry slice of bread

and they will soak it in the rain

and they will scrub it from their heart

so they can move further on

to where the white doves

speak Latin to the sky.

Remembrance

two women wrapped in black

raise their palms, each as if holding a book

and tears fall through a warm whisper

begging the heavens for a little peace

a little peace for all who

lie in silence

on the road to Karbala.

Translations from the Macedonian

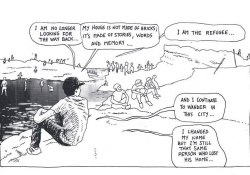

Constantine: I’d like to discuss one of my favorite poems of yours, “Refugees” (Selam aleykum Europe). Could you share with us its background and history?

Al-Asadi: “Selam aleykum Europe” (Peace to you, Europe) is a poem written in the same manner as all my poems, the “transmission” I spoke of before, where I was just a medium through which the poem was written onto paper. I wasn’t setting out to write about anything in particular, but in the back of my mind I saw the troublesome journey of one of my uncles from Iraq, Salem. He came to Greece on a boat five or six years ago, risking his life. Many people, including children, were drowning in the Aegean Sea while attempting to make that crossing. He survived, but once he set foot on the beach, he was taken and severely beaten by the Greek police. He never got the opportunity to secure his documents, although he fulfilled all the criteria for an asylum seeker. Now he lives in Germany, and he’s still an illegal migrant.

Constantine: I felt that it was a particularly personal poem.

Al-Asadi: It was personal, but it was speaking to something beyond the individual as well, those same universal human ideas. “Selam aleykum Europe” is a song about suffering and hope, love and anger, war and peace. The poem strikes against the prevailing supremacist and chauvinistic trends on “The Old Continent.” I wanted to show how a single loaf of bread and white pigeons (the dominant symbols of the poem) can change the way we look at other peoples’ lives and cultivate a more empathic society, one that does not pit one person or people against another.

That idea comes all the more forcefully through the style, which is short and concise. It’s a poetic style that I used in “Under the Dervish’s Hat,” and since then I’ve adopted it as a kind of trademark within the Macedonian literary scene. That concision is something I learned in part from the Macedonian tradition. I can sometimes find a simple semantic solution for a complex syntactic problem within the poems of famous Macedonian poets, such as Aco Šopov, or discover a whole ocean of motifs and themes in a single stanza by Yunus Emre or Mansur al-Hallaj.

But I aim to speak beyond the nation as well: I’m a part of the Skopje Poetry Festival (SPF), the first international poetry festival held in Skopje. As a part of SPF, we organized a movie night with short movies based on poems about Skopje. You might not expect those to have an audience outside of Skopje or Macedonia, but Maria Shakleva’s adaptation of my poem “A Summer Sonnet about My City” made its way to film festivals around the world: at the Poetry Film Tage in Weimar and the International Poetry Film Festival in Los Angeles, among others. And I’ve participated in poetry festivals in Greece, Croatia, and Serbia. There is a personal quality to my poetry, and a national quality, but it is also universal. “Selam aleykum Europe” is, above all else, a protest against the inhumane.

January 2024

Andrej Al-Asadi (b. 1996, London) grew up in Northern Macedonia and is a foremost figure among a new generation of millennial and Gen Z Poets of southern Europe. He has published five books of poetry and two short-story collections, of which Drugo Minato won the 2018 Novite Prize for the best debut in Macedonian fiction.

Viktoras Iliopoulos is a literary translator specializing in Macedonian, Greek, Albanian, and Czech. He has a master’s degree in Balkan studies from Charles University in Prague.

Viktoras Iliopoulos is a literary translator specializing in Macedonian, Greek, Albanian, and Czech. He has a master’s degree in Balkan studies from Charles University in Prague.