Good Storytelling Still Trending: An Interview with Antonia Lloyd-Jones

Antonia Lloyd-Jones has translated works by many of Poland’s leading contemporary novelists, including Nobel Prize winner Olga Tokarczuk, Jacek Dehnel, Mariusz Szczygieł, and Artur Domosławski. She has been a mentor for the Emerging Translator Mentorship Program and co-chair of the UK Translators Association. In 2018 she was honored with Poland’s Transatlantyk Award for the most outstanding promoter of Polish literature abroad.

Veronica Esposito: You’re someone who is able to make a living off of being a literary translator. How do you do it?

Antonia Lloyd-Jones: It’s thanks mainly to good luck and hard work. I went entirely freelance in 2001, but for fifteen years before that, translation was a paid hobby, while I had what I call “sensible” jobs, earning a regular salary. Those jobs allowed me to take out a mortgage and buy property, which means I don’t have to pay rent and can always rent out the place if my work dries up. Part of the secret of financial survival is accepting a wide variety of jobs (good for developing the craft), and although I can afford to be choosy now, I still accept unusual jobs, partly to stretch my skills. These smaller jobs bring in useful income as well as providing variety.

These days I earn a reasonable amount from royalties—I wish I had known sooner how to negotiate contracts properly, and I try to teach less experienced translators how to negotiate the best terms. It’s never easy, and I still get it wrong; it’s like knowing your wish will come true if you get the formula right, but there’s always a catch. I recently heard a translator cry, “Why didn’t I include a TV series based on my translation in my subsidiary rights?” It doesn’t occur to us that world-scale success is possible, but you never know what will take off, and through what medium.

Tokarczuk’s a magnificent storyteller. That’s her superpower.

Esposito: For years, you’ve been an advocate for Olga Tokarczuk, who has now emerged as one of the most prestigious and successful authors in international literature. In your opinion, what makes her so special? What lessons can the translation community draw from the rise of Tokarczuk?

Esposito: For years, you’ve been an advocate for Olga Tokarczuk, who has now emerged as one of the most prestigious and successful authors in international literature. In your opinion, what makes her so special? What lessons can the translation community draw from the rise of Tokarczuk?

Lloyd-Jones: Olga Tokarczuk is an extremely versatile author. I think of her as the Stanley Kubrick of fiction, a writer who thrives on the challenge of adopting a new form for every novel. Myself, her other translator, Jennifer Croft, and her agents were all trying to find a regular publisher in English for her, but publishers were shy of an author who didn’t repeat the same reliable act. However, now her versatility is an attraction. Her writing offers something for everyone, not just by playing with genres but by being psychological and philosophical. There’s a timelessness to her novels; they retain their relevance. For example, Drive Your Plow over the Bones of the Dead (WLT, Winter 2019, 80) is eleven years old but it’s essentially about human rights. The Books of Jacob, her historical epic, is about an eighteenth-century religious sect but also about multiculturalism, colonialism, and how the strong treat the weak. Best of all, she’s a magnificent storyteller. That’s her superpower.

The first lesson for the translation community is that persistence pays off. If you believe in a book, you have to keep pitching it to potential publishers. It’s also important to be open to teamwork. I was lucky to be contacted many years ago by Jennifer Croft, who had fallen in love with Olga’s writing, and politely asked if I minded her publishing some short-story translations. We have shared the role of Tokarczuk’s translators ever since, and it was Jennifer who did the heavy lifting to secure us a publisher at a point when my persistence was waning.

Esposito: You have worked very closely with the Polish Book Institute, and you have incredible connections on the ground in the world of Polish publishing. How have you used these resources as a translator and as an advocate of Polish literature?

Lloyd-Jones: Not many Polish authors have literary agents. Their foreign rights are often represented by the rights department of their Polish publisher. They have a huge task—it’s not easy for them to know each individual market intimately, so they rely on translators to help them to build contacts and to understand foreign book markets. Being in close contact with rights directors means that I’m aware of new books before they’re published. Nowadays there are some more traditional literary agents as well, but they still need help from translators.

I also keep up with developments in Polish publishing through certain reliable sources within the Polish media. Poland has a superb network of summer literary festivals all over the country. I go to some of these regularly, and they’re excellent for new ideas, information about new publications, and the opportunity to meet authors and hear them addressing an audience.

Esposito: What are the most exciting things currently happening in the world of translated literature in the UK?

Lloyd-Jones: Here in the UK there is a visible rise in interest in children’s books in translation, thanks to the efforts of individuals, including (to name just two) those wizards of the translation world, Daniel Hahn and Lawrence Schimel. New initiatives are giving young publishers the confidence to explore translated children’s picture books. Last year Danny took a group of editors to the Bologna book fair for this purpose; and new resources such as the World KidLit website (co-founded by Lawrence, Marcia Lynx Qualey, and Ruth Ahmedzai Kemp) are providing a mine of information for translators and publishers.

There is also more effort to encourage diversity in translation, with a mentorship offered by Tilted Axis press, founded by another wizard, Deborah Smith, for BAME (black, Asian, and minority ethnic) emerging translators, and a project run by the National Centre for Writing aimed at identifying and removing obstacles in the path of BAME translators in the UK.

We also have the annual Translation Prizes event, at which eight prizes for translation from individual languages are awarded (Italian, German, French, Spanish, Dutch, Hebrew, Arabic, and Swedish) as well as the Translators Association First Translation Prize (awarded to the editor as well as the translator). As in the US, prizes are playing an increasing role in publicizing our work and offer a great opportunity to bring it into the mainstream.

Esposito: What books strike you as emblematic of the future of translation?

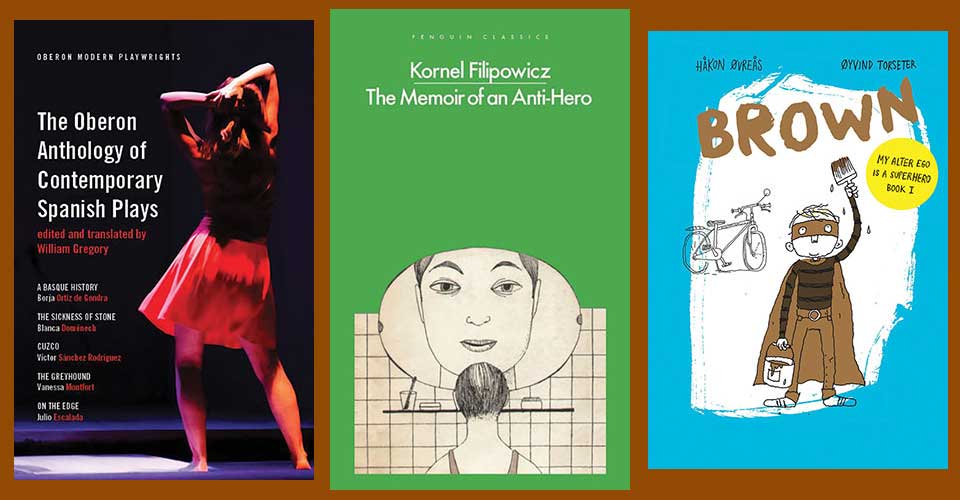

Lloyd-Jones: First, The Oberon Anthology of Contemporary Spanish Plays, edited and translated by William Gregory, which is shortlisted for the Premio Valle-Inclán prize. Drama is underrepresented in translation, and in the UK foreign plays are often staged as “versions,” rewritten by established British playwrights on the basis of fairly literal translations, but at last we’re getting the original authors’ voices through unadulterated, high-quality translations of this kind.

Another recent book I welcomed is Anna Zaranko’s translation of The Memoir of an Anti-Hero, by Kornel Filipowicz (Penguin Classics), because it’s the first translation of a dead author who has been previously ignored in English. It’s a powerful existentialist novella narrated by a man who has used his wits—though not in the most morally impeccable way—to survive the war and its aftermath in Poland. It shows that great literature can still find a wider audience sixty years after it first appeared. I hope to see more lost classics in translation; postwar Polish literature is full of neglected gems.

I hope to see more lost classics in translation; postwar Polish literature is full of neglected gems.

I also hope the revival of interest in children’s books in translation is emblematic of the future: one example is a recent US publication, a translation from Norwegian by Kari Dickson of Brown (Enchanted Lion Books), a middle-grade story by Håkon Øvreås with illustrations by Øyvind Torseter. It’s charming and funny, about a boy who’s finding it hard to be new in the neighborhood until he discovers his own unlikely superpower. This book won the Mildred L. Batchelder Award for YA and children’s books in translation, one of the prizes that’s encouraging children’s book translators and publishers.

Esposito: What is one trend that you think we’ll be paying attention to for years to come?

It’s the great yarns that stay with us and can be reinterpreted over and over again, found to be relevant whatever history throws at us.

Lloyd-Jones: I have no idea how to answer that question without turning it inside out and asking what trend we’ve been paying attention to for years past—what endures, regardless of the state of the world? I think the trend that will survive is good storytelling, just as it has for centuries. It’s the great yarns that stay with us and can be reinterpreted over and over again, found to be relevant whatever history throws at us. The Iliad is still read, studied, retranslated, and reinterpreted in every way imaginable because it’s a very good story that tells us everything we need to know about life. I still read my Andrew Lang Fairy Books because the fascinating stories from around the world are like the keys to human psychology. Stories help us interpret the world but also entertain us. Thank god for translators, who allow us to share them.

February 2020