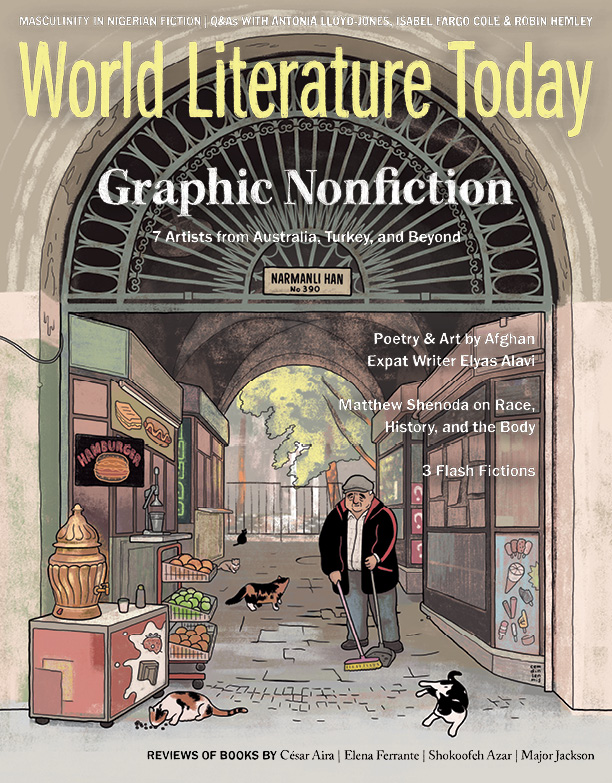

Readers Respond: Graphic Nonfiction

Nonfiction graphic narratives offer readers a powerful window into the lived experiences of the artists and writers who create them. In the hands of the right creator, the synergy of visual and verbal narrative strategies can produce a singular reading experience that cannot be matched by any other form. In response to our query to readers asking which work of graphic nonfiction most challenged or inspired them, we received two consensus choices: Maus and Persepolis. WLT book review editor Rob Vollmar adds three more must-reads along with a note about each of the five titles.

Art Spiegelman

Art Spiegelman

Maus: A Survivor’s Tale

Pantheon, 1997

While there were graphic novels and even autobiographical graphic novels published earlier, Maus was one of the earliest to demonstrate the full potential of the form to tell complex, human stories. In it, Spiegelman mines his father’s stories of surviving the Holocaust while exploring how those experiences deformed and informed their relationship. Drawing upon a rich history in comics of talking animals, Spiegelman deftly handles issues of ethnicity and identity by anthropomorphizing people of varying nationalities as mice, pigs, and cats.

Marjane Satrapi

Marjane Satrapi

The Complete Persepolis

Trans. Blake Ferris, Mattias Ripa & Anjali Singh

Pantheon, 2007

Where Maus is dense and careful, Marjane Satrapi’s Persepolis bursts off the page with youthful energy and fire. The first volume covers Satrapi’s childhood in Iran, historically contexted in the aftermath of the Islamic Revolution of the 1970s. As it becomes plain that her refusal to conform to social expectations for women is not only socially detrimental but dangerous, her parents send her to Europe. The second collection explores her experiences in Europe, eventual return to Iran, and then permanent expatriation to France. While Persepolis was widely read in America as a kind of cry in the wilderness against the patriarchal Iranian government, Satrapi created it as part of a vibrant French bande dessinée movement that foregrounded authentic narratives and multicultural experience.

Shigeru Mizuki

Shigeru Mizuki

Onward Towards our Noble Deaths

Trans. Jocelyne Allen

Drawn & Quarterly, 2011

Onward Towards our Noble Deaths is an anomaly in that it is a self-contained autobiographical story from the Japanese manga tradition that values long, ongoing serial fiction above all else. But what an anomaly it is, recounting Mizuki’s experiences as an unenthusiastic soldier in the Pacific theater in the waning days of the Second World War. Mizuki, who lost an arm and contracted malaria while serving in the Japanese Imperial Army, pulls no punches in depicting the savagery and absurdity of war, captured eloquently in this collection’s title. Originally published in 1973, Onward Towards our Noble Deaths served as a remedial against historians who were trying to rehabilitate Japan’s role as an aggressor in the war. Mizuki’s curious mixture of slapstick humor, meticulous historical research, and brutal realism come together to produce a work that is altogether unforgettable.

Alison Bechdel

Alison Bechdel

Fun Home: A Family Tragicomic

Houghton Mifflin, 2006

If American comics’ infatuation with autobiography reached maturity in Spiegelman’s Maus, it found its pinnacle in Alison Bechdel’s Fun Home. Bechdel brings a sophisticated arsenal of storytelling tools to bear on this complex and wrenching tale of her relationship with her father, whose untimely death and discomfort with his own sexuality shaped her own fearless quest to fully embody her own truth as a lesbian. Full to bursting with literary allusion and sophisticated visual storytelling, Fun Home fulfills the promise of comics as a place for daring truths. In her Q&A in the current issue, Rachel Lindsay discusses the influence of Bechdel’s work on her own.

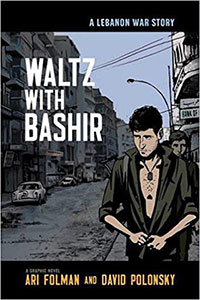

Ari Folman & David Polonsky

Ari Folman & David Polonsky

Waltz with Bashir: A Lebanon War Story

Metropolitan Books, 2009

Concurrently produced and released alongside an animated film of the same name, Waltz with Bashir details Folman’s quest to recover repressed memories of a traumatic event that had occurred while he served in Lebanon during the civil war of the 1980s as a member of the Israeli Defense Force. Folman gives the reader all the historical and social context necessary to appreciate the specificities of the conflict of which he was both an observer and a participant. Alternately stark and lyrical in its re-creation of the surreal violence of the time, Waltz with Bashir is a sobering testament to the deep and lingering scars that war leaves on perpetrator and victim alike.