5 Questions for Devika Rege

Devika Rege’s novel Quarterlife (Liveright, 2024) is populated with millennials who are discovering who they are and what they’re for in what is sometimes called “the New India.” The novel was a finalist for and won multiple awards in India and was recently hailed by the Wall Street Journal as “the best debut of the year.”

Q

Quarterlife begins after India’s 2014 national election, which the Hindu nationalists won. A welcome sign at the airport reads Indian at Heart, Global in Spirit, and Naren says, “People voted for development under a strong leader. The day after the election, the stock market hit an all-time high!” But to himself, he thinks of this postelection period as his country’s “clumsy puberty.” Another character, Ifra, says, “The West never felt like home, but since the election, home doesn’t feel like home either.” Can you talk a bit about the New India as a frame for the novel?

A

The term New India has had many lives. Prime ministers have used it when the country first broke free of colonial rule, and again in the 1990s, when our markets were liberalized in the hope of India becoming a global economic power. In the past decade, Narendra Modi has brought it back to symbolize a dream of financial and technological progress and a society whose cultural bedrock is Hindutva.

Quarterlife is my attempt to examine, through the medium of fiction, the psychological and systemic roots of this political shift. It felt important to me to understand what made the Hindu right so attractive to large swathes of middle- and lower-middle-class Indians. While the fallouts of globalization and neoliberalism have been widely documented, I also wanted to explore the particular form that ressentiment has taken in this century, with the emphasis on identity taking precedence over broader socioeconomic and ecological concerns.

Q

What was your research process for this novel?

A

I spent years shadowing young people across the political spectrum. Among them were volunteers from right-wing organizations, activists branded as antinational, and corporate interns who cared for neither. The insights of value rarely came from formal interviews but from watching these people emerge over time. That meant following them into their homes and offices, observing what their life choices revealed about their beliefs, and listening for how the rhetoric around their desires evolved.

The Indian anthropologist Angana Chatterji recently described Quarterlife as “an ethnography in dissent.” She was being generous, of course, because the term “research” doesn’t quite capture how open-ended and intuitive the process was. I was also living in the country as a citizen, and the novel grew as much through a steady osmosis of personal experience, chance encounters, constitutional debates, news articles, and more sources than I can recall. Just how this material, the narrative design, and the writer’s imagination come together is impossible to parse in retrospect.

Q

While searching for his heritage, Rohit visits Pune, the city you’re from, described in the novel as “the pearl of the Orient, the Queen of the Deccan, the Oxford of the East.” Where in this city do you find inspiration? Where are your favorite spots?

A

These sobriquets speak to what Rohit, a cosmopolite from Mumbai, is hoping to find in Pune. The “Queen of the Deccan” was used by the British to describe the city built by its erstwhile Hindu rulers. Nehru, during his first term as prime minister, called Pune the “Oxford of the East” for its many famous universities. And the “Pearl of the Orient” refers to Manilla, not Pune, though Rohit would like to believe otherwise. When he gets there, he is terribly let down. He learns that the Hindu relics have a bloody and brief history and that the city’s intellectual culture, never free from casteism, has given way to malls and IT hubs. This frustrated desire for authenticity and cultural pride makes him vulnerable to the thrall of Hindu nationalism.

Although Rohit gives it a miss, one of my favorite haunts is a hill called Vetal Tekdi. It is at the center of the city, and environmentalists have been struggling to protect it from realtors. Vetal refers to a ghost, and the wilderness there is beautiful in a wan, almost spectral way. But it’s home to a lot of local birds, and there is an abandoned quarry at the summit over which you can see the most magnificent sunsets.

Q

What in literature and culture has your attention at the moment?

A

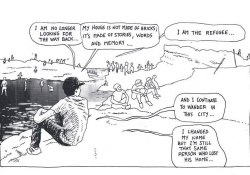

We are a year into a genocide that is being recorded firsthand by its victims and shared worldwide, yet the violence escalates. This is not only about Jewish lobbies in the US. This is a far wider malaise, and it is evident in India, where our government buys arms from Israel and sends thousands of laborers there to assuage our jobs crisis, yet what is happening in Gaza is “not our problem.” Perhaps our anemic response has to do with how broken and exhausted dissent is, or that we are distracted by consumerism, or the crude conviction that nations act only in self-interest, or the global dehumanization of Muslim civilians that has found its dénouement in this hellish hour.

We are a year into a genocide that is being recorded firsthand by its victims and shared worldwide, yet the violence escalates.

I’ve had Indian friends ask me where I was on 9/11. Why are the lives of Palestinians not as real as American lives? And I’ve been thinking about how a society is drip-fed hate and apathy until it has nothing more to offer than a sorry shrug when a father holds up what’s left of his son’s remains in a shoe box. How can you not see your own child in that shoebox? This is the question that all literature and culture has to answer for today.

Q

What is the task of a novel, and is there a novel that comes to mind that serves as a good illustration of this?

A

The novel is too versatile a form to be defined by any one task or title, but when I think of the great novels of any era, an attribute that cuts across is their ability to observe human motivation in their times with exceptional clarity. This clarity extends not only to what is perceived but also how it is rendered. A novel whose progressive themes and poetics are not aligned will be inferior to one in which they are synergistic. Such a representation of the world in a form or pattern that in turn re-creates the world is precisely what is meant by an idea. These days, the novel is under pressure to eschew ideas, both from academics guarding their turf and corporate publishing that cares only for numbers.

To justify irresponsibility in the name of artistic freedom cheapens the meaning of both art and freedom.

Novelists in turn have been lulled into thinking that they are mere storytellers. To my mind, this constitutes a dangerous naïveté about one’s own potential and effects. All art forms reconfigure material from the world in new, imaginative ways, but the novel, on account of its scale, is more dependent on real-world material and is therefore more susceptible to reproducing its malcontents. So, it is all the more important, in hours like these, that novelists are careful what they spawn. To justify irresponsibility in the name of artistic freedom cheapens the meaning of both art and freedom.

Devika Rege was born in Pune, India. She is a graduate of the universities of Mumbai and Iowa. Quarterlife is her debut novel.