Translating Manga

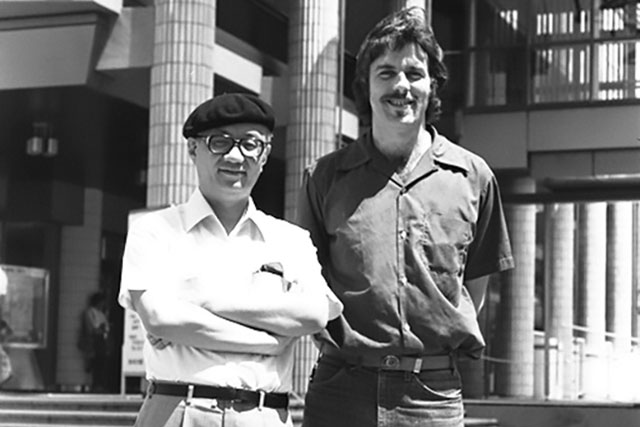

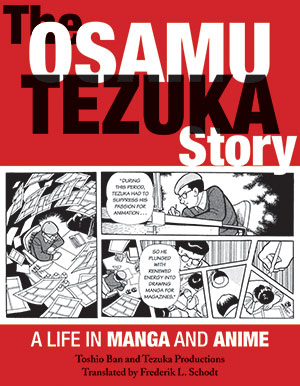

I’ve translated manga off and on for nearly forty years, and it is hard to imagine any translation process that has changed more radically in that time. In Japan, the term manga can mean single-panel cartoons, newspaper comic strips, comic books, graphic novels, and occasionally animation. Yet most non-Japanese associate it with “comic books” or “graphic novels.” Niche translation experiments started in the 1970s, but in North America commercial ventures didn’t succeed until the late 1980s.

In the beginning, few Americans had heard of manga, so “localizing” them was a challenge. Text in speech balloons, of course, had to be translated. But entire pages also had to be mirrored, or “flopped,” so they could be read in “Western” order, top left to bottom right. Early efforts deliberately chose male-oriented action-adventure and sci-fi stories, broke longer works into short episodes, printed them on American comic-book-size paper, professionally hand-lettered dialogue (instead of using printed text, as in Japan), censored some sections, and occasionally attached American-style covers drawn by US artists. Marvel’s 1988 version of Katsuhiro Ōtomo’s Akira even colorized pages to make normally monochrome manga look more like American comics. Words like futon, tatami, fusuma, and shoji required translators to add explanatory footnotes, incorporate explanations into the text, or blur the English. Japanese honorifics, denoting hierarchy, were eliminated. Many early translators also worked with “co-translators” or glorified editors who massaged prose into a uniquely American comic-book style.

Manga is now big business in North America, and knowledge of manga and Japan among fans has increased exponentially. In the new millennium, publishers have largely stopped “flopping” pages to save money and to mollify Japanese artists and American ultrafans who crave “authenticity.” There is also a movement to refrain from translating “sound effects” as well as name suffixes like “-san,” “-sama,” “sempai,” and “sensei,” since experienced readers enjoy Japanese honorifics and hierarchy. Words like futon, tatami, and even “onii-sama” (older brother) are often left as-is. And one result is a weird hybrid of American “comic books” and “Japanese manga” because readers now turn pages and read panels in Japanese order (right to left), but read English text inside panels in English order (left to right).

The role (and pay) of professional manga translators has also changed radically. Manga are now global, in a “good enough” Internet age. Groups of fans translate their favorite manga and, with the use of scanners and Photoshop, post them for free on the web in a piracy process called “scanlation.” Japanese publishers, late to address this issue, now sometimes release manga on the web with translated versions, nearly at the same time. Others have tried to co-opt the scanlation movement and utilize the low cost and speed of fan efforts. As someone who also works as an interpreter in high technology, I suspect that in another ten years or so professional translators will probably be largely eliminated from the actual translation process and function more as stylists, editors, and checkers. It’s a new world.