Editor’s Note

. . . we sleep in the tents of the prophets . . . sing so that distance may forget us. . . . Ours is a country of words.

– Mahmoud Darwish, “We Travel Like All People,” trans. Fady Joudah, in Unfortunately, It Was Paradise (2013)

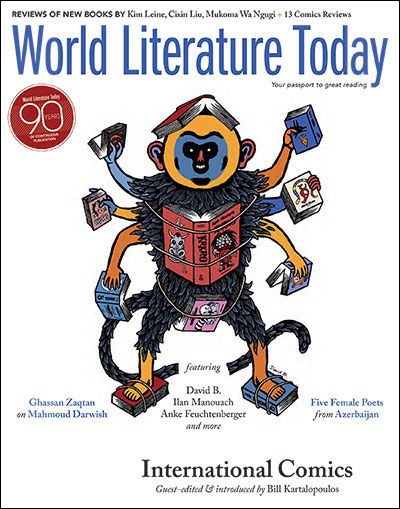

In “We Were Born in the Houses of Storytellers,” the latest installment in the 2016 Puterbaugh Essay series, Ghassan Zaqtan reflects on the achievement of his longtime friend, Palestinian poet Mahmoud Darwish, one of the “towering trees” of contemporary poetry (page 31). Zaqtan, in his own right—a two-time finalist for the Neustadt International Prize for Literature (2014, 2016)—is one of the foremost Arab poets of his generation. In his essay, he offers both “a definition of the Arab poetic achievement” since the 1950s and “a defense of it at the same time.” Fady Joudah, who has translated both Darwish and Zaqtan into English, calls it “a stunning, important narrative.”

Darwish was first profiled in these pages in Mohammed Bakir Alwan’s essay “Contemporary Palestinian and Jordanian Literature: Fractured Vision,” in which the author notes the importance of such poets as Ibrahim Tuqan and Salma Jayyusi before focusing on three “poets of Resistance”: Darwish, Samih al-Qasim, and Tawfiq Ziad (Books Abroad, Spring 1972). Alwan points out that many of these writers were prolific translators, introducing works by Eliot, Faulkner, Hikmet, and other modernists into Arabic. Darwish is credited with writing “beautiful love poems” as well as “defiant and revolutionary” verse. In a review of an early edition of Darwish’s Selected Poems (1973), translated by Ian Wedde and Fawwaz Tuqan, Suhail ibn-Salim Hanna acknowledges “the power lurking in Darwish’s poetic voice,” his “revolutionary message,” and the twentysomething poet’s “brilliant use of irony” (Books Abroad, Autumn 1974).

Zaqtan, for his part, while paying homage to Darwish, also invokes the Nakba of 1948, when his parents were evicted from their ancestral village of Zakariyya, in Hebron, after which they moved to Beit Jala, south of Jerusalem, where Zaqtan was born in 1954. For thirty years, Zaqtan lived in refugee camps in the West Bank and Jordan. A half-century later, the return of Zaqtan with his mother and aunts to their village is commemorated in his poem “Four Sisters from Zakariyya,” yet in the poem—and in the photo reproduced here—we do not see “the house of the storytellers,” only the four sisters in black shawls silhouetted against the landscape, reading “soaked letters” while clouds “slowly pass through the canyon.” This poem is included in Zaqtan’s Griffin Prize–winning collection Like a Straw Bird It Follows Me (2012), which represents the author’s lifelong attempt to “demythologize exile and dispossession,” according to Joudah, and “transform loss into a life-giving force.”

Returning to Darwish, Zaqtan insists that “knowledge and culture must structure a text from the inside and take the place of the prevailing rhetoric,” Salafist or otherwise. Focusing on this “inside text” at the heart of Darwish’s poetics, “we are able to extend the reading of our existence,” writes Zaqtan, “in the light of resistance.” Like his predecessor, and in such poems as “This Is My Only Profession,” Zaqtan chooses “to author a bend in the story / so we can prolong the evening / or make predictions / and matters bearable.” From his position as both outsider and insider in this “other geography . . . other history . . . other culture,” having “returned from the heart of the text,” Zaqtan reminds us that in the face of latter-day extremes of rhetoric, violence, and shatat (dispersal), poets—while no longer prophets—“stroll behind the narrative,” bending the story so that we might hear it anew.

Daniel Simon