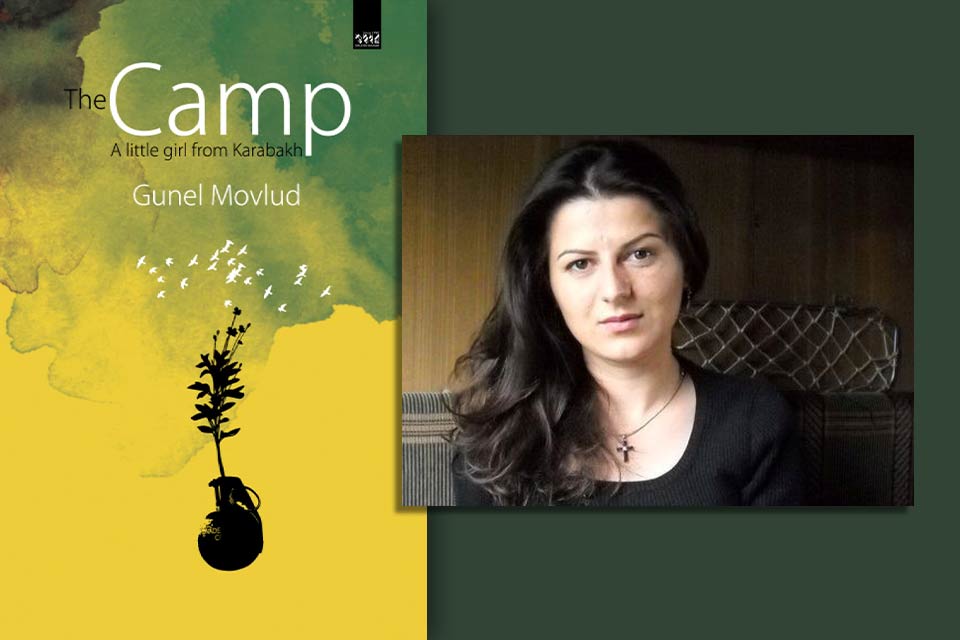

Unspoken Realities of Displacement: Gunel Movlud’s The Camp: A Little Girl from Karabakh

In her semi-autobiographical novel The Camp: A Little Girl from Karabakh (Shuddhashar, 2022), Gunel Movlud refers to her life as an internally displaced person during the First Nagorno-Karabakh War (1988–94). Twelve-year-old Gunel and her family flee their home village in Azerbaijan’s Jabrayil District and find refuge in a tent city in Sabirabad District, directly bordering Iran. Here, she spends five years amidst poverty, disease, gender-based oppression, and injustice and navigates new social hierarchies forming between people stripped of their land, possessions, and identities. In this coming-of-age story, young Gunel struggles to overcome the limitations of being a refugee—financial hardships, societal pressures, limited access to education—and find her place in life.

In her semi-autobiographical novel The Camp: A Little Girl from Karabakh (Shuddhashar, 2022), Gunel Movlud refers to her life as an internally displaced person during the First Nagorno-Karabakh War (1988–94). Twelve-year-old Gunel and her family flee their home village in Azerbaijan’s Jabrayil District and find refuge in a tent city in Sabirabad District, directly bordering Iran. Here, she spends five years amidst poverty, disease, gender-based oppression, and injustice and navigates new social hierarchies forming between people stripped of their land, possessions, and identities. In this coming-of-age story, young Gunel struggles to overcome the limitations of being a refugee—financial hardships, societal pressures, limited access to education—and find her place in life.

Following the collapse of the Soviet Union in 1991, Azerbaijan suffered from severe poverty, social disintegration, and political instability and went through “the poorest period in the country’s history.” The period also witnessed a series of territorial and ethnic disputes among the former Soviet republics. The Nagorno-Karabakh conflict, the first and the longest, resulted in thousands of civilian deaths and the displacement of hundreds of thousands of people. Life in the refugee camp in the novel, lacking formal law and ruled by “unspoken rules,” mirrors the collapse of a “civil” society in the country and can corrupt human nature.

Movlud’s prose, as translated by Zeyneb Rzazade—simple and straightforward and perhaps lacking a poetical depth—reflects the honesty and rawness of her experiences: “Those who romanticize poverty and misery irritate me. When people who have not slept on the floor or starved a day in their lives, but rather always had a variety of food in their fridges, try to find beauty and art in calamity and poverty, they insult the struggles faced by me and innumerable other people who have experienced a refugee’s life.”

The narrative primarily follows young Gunel and her family’s journey, but rather than adhering to a traditional plot, its fragmented structure diverts to reconstructed memories about other residents’ lives. Details on the historical background of 1990s Azerbaijan and daily life in the camp allow readers to dive into the intricacies of refugee life beyond formal reports, reminding us that life is woven out of such small personal moments.

The novel shows humans’ ability to adapt to harsh conditions and create stability and routine out of uncertainty. Initially, many residents live in disbelief and denial, clinging to the hope that their situation will be temporary. They are reluctant to improve their living spaces, invest in furniture, take care of the environment, and disregard hygiene. Years later, as the camp moves from Iranian to German patronage, their denial turns into acceptance: families plant gardens, build more sustainable houses, and even hold marriage ceremonies.

Many men in the camp struggle with fear of emasculation as a consequence of displacement. Blamed for losing their homeland and having no prospects in life without a house or a job, they failed in their traditional roles as providers and protectors. The feeling of worthlessness leads to alcoholism and depression, manifesting in destructive and abusive behavior as men desperately try to cling to patriarchal structures. The residents form new hierarchies as camp representatives (camp residents responsible for distributing food and clothes to their groups for additional aid) abuse their power, indulge in corruption, and use human suffering to accumulate wealth.

Sexual abuse and rape permeate the reality of the refugee camp, but it remains unspoken as victims are silenced by social shame and no hope for justice. Overcrowding and lack of privacy in the camp leave women, especially single and disabled, vulnerable to gossip, discrimination, and abuse. In her accounts, Movlud tells the stories of both the abused and the abusers, showing how and why society chooses to ostracize the victims instead of protecting them.

As a work of feminist literature, The Camp explores gender and power dynamics in the tent city.

As a work of feminist literature, the novel explores gender and power dynamics in the tent city. In Azerbaijani society, women are considered to embody family honor and dignity, while all female issues are expected to remain secret and private. Life in the camp amplifies this pressure on women. It turns simple daily activities such as using the toilet, taking a shower, or having periods into an immense challenge as they must constantly hide from the judging male gaze. The first scene opens with Gunel’s father slapping her across the face for saying, “I love nature.” In his eyes, a girl sounding too educated or mature signifies the threat of “becoming a father of a loose girl” and discrediting his male honor. After experiencing the violence, the young girl is more worried about staining her clothes with blood and angering her mother; just like many other girls and women, she is concerned about being an inconvenience. Gunel’s grandmother does not fear being an inconvenience: she openly goes against the camp’s and society’s “unspoken rules” and stands out as a defiant character.

It is also the strength of women that sustains the camp. They work tirelessly in the cotton fields to overcome poverty and transform clothes received as donations into practical winter garments to keep the children warm and survive cold winters. The novel does not only focus on the negative. Amid the camp’s harsh realities, moments of self-sacrifice and communal support emerge as silver linings, when humanity and compassion prevail as people come together to pull through difficult times.

The Camp is one of the few, if not the only, refugee narratives in Azerbaijan, especially considering how rarely the country’s contemporary works are translated into English. In its homeland, the novel was criticized for the absence of the word “Armenian,” for not pointing fingers at the enemy or seeking the guilty. I believe that this attitude overlooks the book’s main message: “War is immoral!” It is a testament to human suffering as a dire consequence of war: blame offers no relief, but the resilience of the human spirit does.

The Camp is a testament to human suffering as a dire consequence of war: blame offers no relief, but the resilience of the human spirit does.

I recommend this book to readers seeking to diversify their perspectives and broaden their understanding of displacement. It covers the issues of human rights, feminism, and refugee life and gives insight into the post-Soviet space and its affairs. At first sight, Azerbaijan today is different from the Azerbaijan of the past described in the novel: gone are the poverty, political turmoil, and uncertainty as well as the tent cities. The Second Nagorno-Karabakh War may be over, but it creates similar repercussions: more displaced people, human casualties, and suffering. The issues raised in the novel remain relevant to Azerbaijani society, and a lot of work needs to be done to turn the Karabakh question from an open wound to a wound hoping to heal.

About the author

Gunel Movlud is a journalist, writer, poet, and translator from Azerbaijan. She has lived in Norway since 2016 after being pursued as a journalist. As a child, she and her family fled her hometown in Nagorno-Karabakh as Armenian forces occupied it as a result of the war. Her novel The Camp: A Little Girl from Karabakh has been translated into English, Norwegian, Georgian, and Russian. Among her other published literary works are her books of poems Darkness and Us (2004), 5XL (2011), Response to the Late Afternoon (2013), and Marina (2019). Her writing focuses on key social issues such as women’s rights, human rights, gender equality, democracy, and peacekeeping.

University of Oklahoma