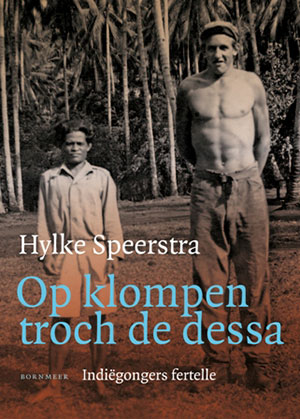

Op klompen troch de dessa by Hylke Speerstra

Gorredijk, Netherlands. Bornmeer. 2014. ISBN 9789056153359

Friesland’s best-selling author has done it again; this time a collection of stories from survivors of the ill-advised and ill-fated attempt by the Dutch government to maintain colonial control of Indonesia. Shortly after the end of World War II, the Dutch sent one hundred thousand of their young men, many of them still in their teens, to gruesome combat in the jungles and rice fields of Indonesia. They went ill-prepared and ill-equipped. (The book’s title alludes to that: In wooden shoes through the rice fields.) They left behind siblings, parents, girlfriends, fiancées, and dreams of a future. Led to believe that they were fighting for a just cause, they discovered that they had been betrayed, that they were rather engaged in a guerilla warfare that would continue to haunt them with its shame and guilt.

Friesland’s best-selling author has done it again; this time a collection of stories from survivors of the ill-advised and ill-fated attempt by the Dutch government to maintain colonial control of Indonesia. Shortly after the end of World War II, the Dutch sent one hundred thousand of their young men, many of them still in their teens, to gruesome combat in the jungles and rice fields of Indonesia. They went ill-prepared and ill-equipped. (The book’s title alludes to that: In wooden shoes through the rice fields.) They left behind siblings, parents, girlfriends, fiancées, and dreams of a future. Led to believe that they were fighting for a just cause, they discovered that they had been betrayed, that they were rather engaged in a guerilla warfare that would continue to haunt them with its shame and guilt.

Hylke Speerstra, as he had done with Dutch emigrants who after World War II scattered across the globe (Cruel Paradise, 2005), searched out survivors of this dark chapter in Dutch history and gathered their stories. The story, for example, of Ale van der Meer who in the Depression years worked for a pittance, was picked up by the Germans in World War II and sent to a forced-labor camp (from which he walked back at war’s end weighing less than a hundred pounds), was pressed into military service and sent to Indonesia not long after that, became part of a firing squad carrying out executions, and shot a suspected sniper who turned out to be a young lad of twelve or thirteen: memories that tore at his soul the rest of his life.

Survivors break their long silence in these stories. In the words of one: “I’m eager to break the silence. I always kept it to myself, and it was as if I had built a wall around myself. But at last the wall collapses.” And the painful memories surface: of mass killings, including women and children; beheadings; finding the shallow graves of thousands of fallen young soldiers; officers without a conscience sending their men into war-crime scenarios; seeing best buddies die; leaving behind lovers and their children when a political settlement was finally reached and they returned home. But what happened in the jungles of Indonesia came home with them, and they would never be the same.

More than five thousand did not come home. Speerstra visits those stories, too, of bereaved parents whose grief never went away, or of fiancées who waited in vain. And though there is an inevitable similarity running through these stories, no two are the same. Speerstra’s storytelling powers are fully exercised here by varying the narrative techniques and by letting each subject tell his story in his own unique way. Characteristically, the author allows the stories their emotional dimension. In many of these stories, he listens to the heartbeat of a lost generation; in recording them, he makes sure that the war and its cost are no longer forgotten.

Henry J. Baron

Calvin College