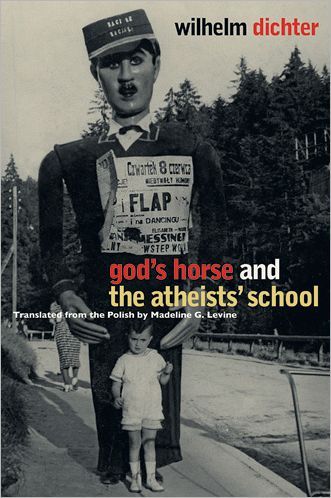

God’s Horse and The Atheists’ School by Wilhelm Dichter

Madeline G. Levine, tr. Evanston, Illinois. Northwestern University Press. 2012. ISBN 9780810127937

After a distinguished career as a ballistics and algorithms patent holder, Wilhelm Dichter started writing. In his work of the past twenty years, he not only realized his childhood dream but also overcame the Holocaust’s legacy of death and suffering. The two autobiographical novels under review, God’s Horse and The Atheists’ School, resonate with each other. The central part of this narrative is the portrait of a little boy hidden in attics, inside wells, and under beds, barely surviving war on the run. An imaginative little boy filled with a complex and precocious inner life, and gifted with phenomenal observation powers, who finds solace in books and pictures. A little boy with thick glasses and achy knees, who gives his brand-new soccer ball to street chums and watches their game from the sidewalk. A normal little boy whose looks, clumsiness, and absentmindedness in normal circumstances would make him a punching bag, but whose sufferings are defined by wartime and postwar Poland’s anti-Semitism. A little boy who learns a healthy skepticism toward reality and is able to silence his needs and complaints. Told in a dispassionate tone, his story creates perspective and space to appreciate the full span of the child’s emotions.

After a distinguished career as a ballistics and algorithms patent holder, Wilhelm Dichter started writing. In his work of the past twenty years, he not only realized his childhood dream but also overcame the Holocaust’s legacy of death and suffering. The two autobiographical novels under review, God’s Horse and The Atheists’ School, resonate with each other. The central part of this narrative is the portrait of a little boy hidden in attics, inside wells, and under beds, barely surviving war on the run. An imaginative little boy filled with a complex and precocious inner life, and gifted with phenomenal observation powers, who finds solace in books and pictures. A little boy with thick glasses and achy knees, who gives his brand-new soccer ball to street chums and watches their game from the sidewalk. A normal little boy whose looks, clumsiness, and absentmindedness in normal circumstances would make him a punching bag, but whose sufferings are defined by wartime and postwar Poland’s anti-Semitism. A little boy who learns a healthy skepticism toward reality and is able to silence his needs and complaints. Told in a dispassionate tone, his story creates perspective and space to appreciate the full span of the child’s emotions.

At school, Dichter becomes known for his drawings of “little people”—his heroes, Pan Tadeusz, Sienkiewicz’s hussars, the Punic Wars, post-German military magazines, and David Copperfield—defenders or avengers, surrogate, recyclable family helping to right wrongs and conjure fear. This re-created safety net enables the child to keep his balance in a deranged universe. Balance is usually achieved through incremental positioning—in Dichter’s narrative, the segments of his experience are brief, disconnected elements separated by blank spaces. The result is a transcendental story. To use another image, Dichter choreographs a theater of shadows, casting himself partly in the light and partly in the shadow in order to partake of life and commune with the dead.

The outer world presented by Dichter is strikingly insightful and accurate. Not unlike other displaced or persecuted children, he spends a great deal of time describing humble objects that sustain soul and body, namely books, food, and memories. The adults around him recite poetry, speak German, Yiddish, Russian, Polish, English, and French. They represent the encounter between the Orthodox Galician Jewish world and the sophisticated, assimilated world of Austrian Jews whom the Holocaust trapped in the East. In 1945, communist Poland is a world in “ruins, rags, and lies.” We get a crash course in current events, from the Kielce pogroms to Lysenko, from Chapaev to Stalin’s seventieth birthday, from drunk party officials to the building of the Palace of Culture. We get a rare glimpse into the network of surviving Jewish Polish families and into the dilemmas of being Jewish in postwar Poland. We see the old, sincere ideologue, Pan Rosenthal, and the young rising communist leader spar about politics. Then, one by one, surviving brothers, sisters, friends, and cousins come back and then leave for Munich, Tel Aviv, New York. A family imprisoned and broken apart by war comes back to life as Dichter comes of age.

Alice-Catherine Carls

University of Tennessee at Martin