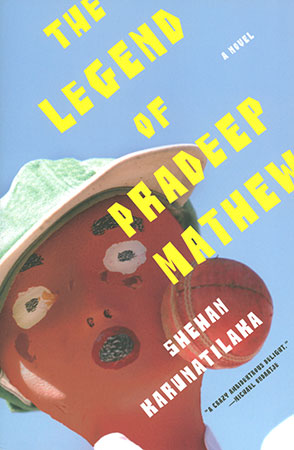

The Legend of Pradeep Mathew by Shehan Karunatilaka

Minneapolis. Graywolf Press. 2012. ISBN 9781555976118

Minneapolis. Graywolf Press. 2012. ISBN 9781555976118

Shehan Karunatilaka’s first novel brilliantly exemplifies the best capacity of contemporary literature to make the stuff of local lives absolutely relevant, indeed necessary, to readers all over the world. W. G. (Wije) Karunasena, a rapidly aging alcoholic sportswriter obsessed with cricket, spends his last days in Colombo, Sri Lanka, writing scripts for a series of films about Sri Lanka’s greatest cricketers and researching a book about the enigmatic bowler Pradeep Mathew. The films go largely unwatched because of power cuts, and the book remains unfinished at the time of Wije’s death. Such disappointments are not unusual for Wije. Although recognized as Ceylon Sportswriter of the Year in 1969, he sums up an uneven career—“I had won a few more awards, done a stint in radio, been sacked twice from reputed newspapers and acquired a reputation as a belligerent drunk”—that extends to his personal life, marked by petty quarrels, heavy drinking, a strained marriage, and estrangement from his son. During his best moments, Wije shows calm insight into his own condition: “There are things that Sheila will never know. She will never know how much I regret. She will never know that I disappoint myself more than I disappoint her. She will never know that even though I love her more than anything, I will always hate myself a tiny bit more.”

Written with humor, pathos, empathy, bittersweet cynicism, and bittersweet hope, Karunatilaka’s novel deftly balances the claims of the local and the expectations of the universal. Most explicitly a novel about cricket, complete with statistics, lists of the greatest players, discussions of test matches, descriptions of bowling deliveries, and reports of the cutting insults exchanged among players, the novel deftly leads the reader into its primary setting of Colombo and the contemporary history of Sri Lanka and its fractured society. At the same time, The Legend of Pradeep Mathew addresses numerous dimensions of the human condition that belong to all localities. This novel is as much about love, death, dependency, obsession, hope, fulfillment, and despair as it is about cricket. Karunatilaka brings the local and the universal together in compelling passages: “Explain the differences between Sinhalese and Tamils? I cannot. The truth is, whatever differences there may be, they are not large enough to burn down libraries, blow up banks, or send children onto minefields. They are not significant enough to waste hundreds of months firing millions of bullets into thousands of bodies.”

Read this book if you are interested in cricket, Sri Lanka, or South Asian anglophone writing. More urgently, read this book if you want to know what it means to be human in a complex, changing, challenging, and sometimes rewarding and enriching world.

Jim Hannan

Le Moyne College