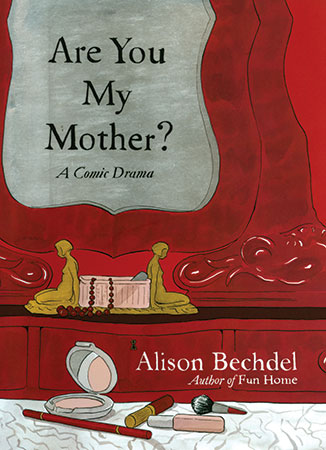

Are You My Mother? A Comic Drama by Alison Bechdel

Boston. Houghton Mifflin Harcourt. 2012. ISBN 9780618982509

Boston. Houghton Mifflin Harcourt. 2012. ISBN 9780618982509

Alison Bechdel made an auspicious entrance on the literary scene with her first graphic memoir, Fun Home: A Family Tragic Comic, in which she excavates her relationship with her father. That remarkable work was filled with literary allusions (her father was a high school English teacher) and revelations about the family dynamic. In this new graphic memoir, Bechdel spends most of the book exploring her relationship with her mother and a variety of female lovers and female therapists.

Sadly, for the reader, the mother-daughter relationship is not as engaging as the father-daughter interaction was in the earlier work. In addition, Bechdel’s use of other literary and psychoanalytic works is less wide ranging here and doesn’t have the resonant quality so remarkable in Fun Home. She is drawn mainly to the work of British psychoanalyst Donald Winnicott and to Alice Miller’s Drama of the Gifted Child, and there are many scenes here with Alison in therapy with a variety of therapists. Her statement to one of them about her inability to write unless she gets her mother out of her head and the concomitant admission that the only way to get her out of her head is to write the book, presents the Catch-22 and raison d’être of this work.

Bechdel and her character Alison are also steeped in the literature of both feminist theory and liberation; in fact, when she alludes to Virginia Woolf or Adrienne Rich, or explores her need for creating art, this novel achieves some of the power of her earlier work. But all too often she gets mired in the working through of her life against Winnicott’s theories, and this adherence to explanation stalls the work’s power. At times it comes close to reading like a graduate thesis about object relations, Winnicott’s field.

Bechdel has great skill in depicting characters, both graphically and through language, and she makes artistic leaps that are at times breathtaking. Her creative use of graphic chiaroscuro and her deft use of panels of varying dimensions engages the reader with the text and entices one to jump across gutters to create what Scott McCloud, in Understanding Comics, refers to as “closure.” In other words, there are many delights here, but this graphic memoir fails as a truly coherent work because of what feels, at times, like intrusive pedantry.

Rita D. Jacobs

Montclair State University